Why we have an inheritance tax

The House of Representatives recently voted to eliminate the estate tax. Because of the recent vote, the topic may come up in conversations with people you know.

This is an easy case to “win” because there is such a strong moral case for inheritance taxes and it’s also a great opportunity to practice talking about what you believe.

Most of what you’ll see in the media, however, consists of the “strong” moral case for corporate special interest groups and a “weak” response. By weak response, I mean a case that doesn’t talk about the morality of the estate tax. A case that is often simply the negation of conservative arguments. A moral case should explain ‘why’ we believe in inheritance taxes.

To start, I believe …

1. Privilege should be earned (not inherited).

To paraphrase Teddy Roosevelt, every dollar received should represent a dollar’s worth of service rendered – not gambling in stocks.

Roosevelt said it better:

No man should receive a dollar unless that dollar has been fairly earned. Every dollar received should represent a dollar’s worth of service rendered — not gambling in stocks, but service rendered. The really big fortune, the swollen fortune, by the mere fact of its size acquires qualities which differentiate it in kind as well as in degree from what is possessed by men of relatively small means. Therefore, I believe in a graduated income tax on big fortunes, and in another tax which is far more easily collected and far more effective — a graduated inheritance tax on big fortunes, properly safeguarded against evasion, and increasing rapidly in amount with the size of the estate.

2. Equal opportunity for current generations.

Adam Smith said this in Wealth of Nations:

When great landed estates were a sort of principalities, entails might not be unreasonable. Like what are called the fundamental laws of some monarchies, they might frequently hinder the security of thousands from being endangered by the caprice or extravagance of one man. But in the present state of Europe, when small as well as great estates derive their security from the laws of their country, nothing can be more completely absurd. They are founded upon the most absurd of all suppositions, the supposition that every successive generation of men have not an equal right to the earth, and to all that it possesses; but that the property of the present generation should be restrained and regulated according to the fancy of those who died perhaps five hundred years ago.

How will the current generation innovate and “create value” if those who’ve come before do nothing but hoard and accumulate?

What resources will future generations have?

3. To prevent dynasties of wealth.

Anyone who’s ever played monopoly knows what inevitably happens, one player gains control of the board.

Now imagine if this control is passed down from generation to generation. What’s it look like for new players on the board?

4. To preserve democracy.

As wealth accumulates, it becomes easier and easier for the extremely wealthy to influence government. This is also referred to as “capture”.

Again, Teddy Roosevelt:

Now, this means that our government, national and state, must be freed from the sinister influence or control of special interests. Exactly as the special interests of cotton and slavery threatened our political integrity before the Civil War, so now the great special business interests too often control and corrupt the men and methods of government for their own profit. We must drive the special interests out of politics. That is one of our tasks to-day. Every special interest is entitled to justice — full, fair, and complete — and, now, mind you, if there were any attempt by mob-violence to plunder and work harm to the special interest, whatever it may be, that I most dislike, and the wealthy man, whomsoever he may be, for whom I have the greatest contempt, I would fight for him, and you would if you were worth your salt. He should have justice. For every special interest is entitled to justice, but not one is entitled to a vote in Congress, to a voice on the bench, or to representation in any public office. The Constitution guarantees protection to property, and we must make that promise good. But it does not give the right of suffrage to any corporation.

In a functioning democracy, money and government should be separate. The purpose of government should be to represent the people and act in the interests of the commonwealth.

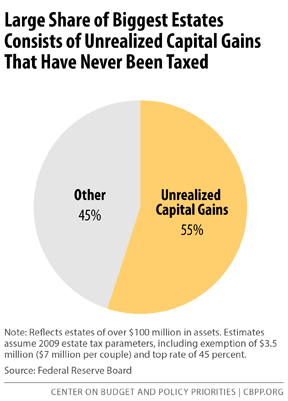

5. Most of the value of large estates has never been taxed.

One of the reasons for enacting the estate tax in 1916 was to close a loophole. The loophole is appreciation. Most of the value of extremely large estates comes from appreciation. That is, value that has increased over time.

An estate worth $1 million in the 1960s would be worth $8 million today. An estate worth $1 million in 1910 would likely be worth far more.

55% of the value in large estates is comes from these unrealized capital gains.

6. Property should be the servant and not the master of the commonwealth.

Wow, Roosevelt said that? :

The true friend of property, the true conservative, is he who insists that property shall be the servant and not the master of the commonwealth; who insists that the creature of man’s making shall be the servant and not the master of the man who made it. The citizens of the United States must effectively control the mighty commercial forces which they have called into being.

7. To promote work and service, not lazy returns.

Conservatives love to talk about incentives. What happens when the thing we incent the most isn’t producing, but simply inheriting and lazy investing?

Sam Fleischacker writing in Salon:

There is, of course, nothing wrong with parents giving their children a good start in life. On the contrary, it is admirable when people devote their earnings to a comfortable home and a good education for their children, and when they give their children ample opportunities to find satisfying work. But all this can be done without, in addition, passing on an estate worth so much that the children need never contribute to society at all. The passing on of such estates creates a large and unnecessary barrier in the way of social mobility, giving the children of the rich an enormous and entirely unearned advantage over the children of the poor.

Responding to objections

Here’s some of the objections you’re going to hear. Most of these can be found in corporate think tank papers that are used as the basis for talk radio stories and conservative talking points.

1. Parents should have the right to do what they want with their money.

This is perhaps the toughest objection to handle because it appeals to our intuitive idea that people should be able to do what they want.

We have all kinds of laws, however, that limit the ability of people to do everything they want. These laws take into account the interests of everyone. We have laws against murder, laws against theft, and laws against cheating people.

What I usually like to do in this situation is ask the following question: Should kings have had the right to pass on their monarchies forever?

Because this is what huge wealth transfer tends to look like. As discussed above, excessive wealth accumulation destroys equal opportunity, prevents innovation, work, and service, and leads to corrupt government.

Another good question to ask is, how much do children need for an equal shot? As Sam Fleischacker said above, it’s easy to provide ample opportunity, it’s quite another thing to create lazy children who contribute nothing back to society and exist solely because of their inheritance.

2. The estate tax will hurt farmers or small businesses.

The current exemption for the estate tax is $5.38 million per person. It is nearly $11 million for a married couple.

According to the Tax Policy Center, only 20 small businesses and farms nationwide owed any estate tax in 2013. Those 20 estates owed just 4.9%.

No farmers or small businesses are harmed.

It does raise the interesting question though, if it doesn’t impact farmers or small businesses, why are people constantly talking about farmers and small businesses?

Is it because giving tax breaks to people who can afford to build $30 million “sporting” estates is morally bankrupt?

3. It reduces incentives to save and invest.

It doesn’t. People have all the money while they’re alive. It has absolutely no effect on incentives because it impacts estates after someone has passed.

You can’t “incent” the dead.

4. We shouldn’t tax money more than once.

55% of the value of large estates comes from appreciation. This is money that has never been taxed.

5. It creates high compliance costs.

Most of these “high costs” are costs that would be incurred anyways that are lumped in as “compliance costs” to inflate the numbers.

According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities:

Exaggerated estimates of estate tax compliance costs often incorrectly include the cost of activities that would be necessary even without an estate tax — hiring estate executors and trustees, drafting provisions and documents for the disposition of property, and allocating bequests among family members, for example. These activities account for about half of all costs sometimes associated with estate planning.

In other words, these costs will exist with or without any estate tax.

6. The wealthy won’t pay any estate taxes anyways because of loopholes.

This is perhaps the oddest argument I’ve heard (though I’ve heard it several times now) and the easiest to deal with.

All you have to do is ask, why not eliminate the loopholes?

What does “win” mean?

Since I used the term “win” in the intro of this piece, I wanted to talk a little bit about what “win” means.

I use the term “win” to mean that you want people on your side. Or, at the very least, you don’t want them fighting on the side of corporate special interests.

What win doesn’t mean is winning some kind of academic argument.

The way to win people over in this manner is to talk about what you believe and why. You don’t win people over by:

- Telling them what to do

- Calling them stupid

- Telling them that they are “wrong”

It also involves listening and acknowledging that people often have valid concerns. So for example, if someone says: “It could hurt farmers,” you want to acknowledge that you share this concern: you don’t want to hurt farmers either. You might say something like:

Good point. Did you know the estate tax only applies to estates worth more than $5.38 million per person? The exemption is almost 11 million for a married couple. This makes sure it doesn’t hurt farmers and small businesses.

In this manner, you’ve acknowledged their concern as valid (which is why corporate special interest groups of course always include farmers and small businesses) and talk about how it was addressed.

Often, people simply won’t know because corporate media always makes the case against inheritance taxes. You can also mention that only 20 farms were impacted in 2013 and that these farms on average paid only 4.9%.

I would also recommend reading Teddy Roosevelt’s speech. He acknowledges all of the conservative concerns of the day. He doesn’t call anyone stupid.

On the contrary, he acknowledges these concerns and shows how to reconcile them:

It seems to me that, in these words, Lincoln took substantially the attitude that we ought to take; he showed the proper sense of proportion in his relative estimates of capital and labor, of human rights and property rights. Above all, in this speech, as in many others, he taught a lesson in wise kindliness and charity; an indispensable lesson to us of to-day. But this wise kindliness and charity never weakened his arm or numbed his heart.

What he is saying is that conservatives may argue solely from the perspective of property rights. Roosevelt reminds us of the human rights side of the equation. How do we value both people and property and in what proportion?

Roosevelt made the moral case for the inheritance tax. He didn’t shy away from it. He didn’t try to message anyone. He said what he believed.

When you do this, you become a leader and you inspire others.

People often sound incredulous when I say that I can usually win 9 out of 10 people. The reason for this is that when they hear “win” they tend to think winning an academic style argument. If I were to try to win this way, I don’t think there’s any way I could say 9 out of 10. I consider winning when someone sees your argument as moral.

Why? People aren’t computers. They don’t make decisions based on facts. They make decisions based on what they perceive as right and wrong.

If you don’t believe me, reach out to a conservative. Or talk to anyone for that matter about politics. Invite someone out for coffee or a beer and talk to them about an issue. Raise it in a friendly way and listen to their position. As you listen, think about why you agree or disagree with this position. Is there a moral reason for it?

Try shifting the way you discuss the issue to what you believe and why. Facts and statistics are great, but you want to use them within a strong moral context. Don’t be discouraged if someone doesn’t “agree” with you immediately. This is unlikely to happen. Acknowledge that it’s unlikely to happen, especially if leading in this fashion is new to you. What’s more likely to happen is that someone does start to see a slightly different side than is usually presented, however.

Listen, don’t get discouraged, and treat every opportunity as an opportunity to practice, learn, and improve.

What I think you’ll find is that if you approach things from the perspective of what is the right thing to do, and/or, how do we solve this together, you will significantly improve your odds.

And yes, there will be people who just want to pick fights. Ignore them, or in the words of a conservative Texan friend of mine, kick them to the side of the curb. Focus on the independents and people who are more open-minded. This also tends to improve your overall well-being as you learn not to waste time in unproductive conversations with people who have no intention of listening.

Examples

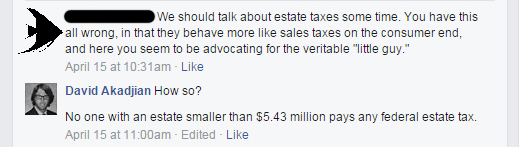

Here’s a couple of examples which came up after I posted a piece entitled 10 tax cuts and who they benefit.

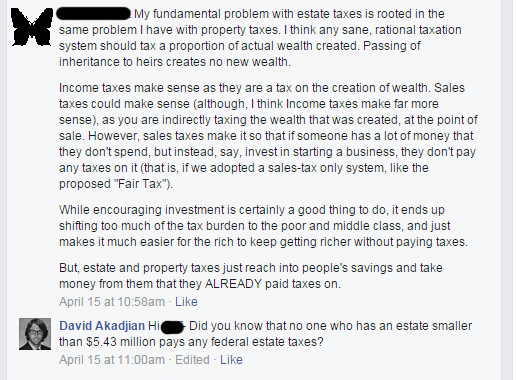

A friend raised the issue. His position that repealing estate taxes benefits the little guy somehow struck me as strange. So I thought I’d ask.

Before I could find out though, another friend jumped in. He stated the common moral objection that people have already paid taxes on property and estates.

I should have brought up that this isn’t the case, that property and estates increase in value and that these capital gains wouldn’t see any taxation otherwise.

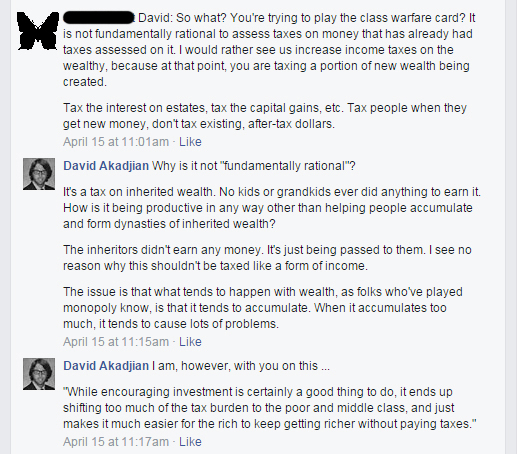

Instead I asked him if he knew about the $5.43 million cap. Butterfly responded by accusing me of class warfare. This is another frequent tactic to make the wealthy look like “victims” of mean liberals.

Any time someone says something is “rational” what it tends to mean is that it agrees with their moral belief. Instead of accusing him of anything back, I stated my moral belief: inherited money is not earned money.

I also made sure to talk about how I agreed with his statement about investing. Why? Well, I also agree we should be investing and I also think the tax burden is being shifted to the middle class and poor. Of course, I believe part of this shift is eliminating the estate tax.

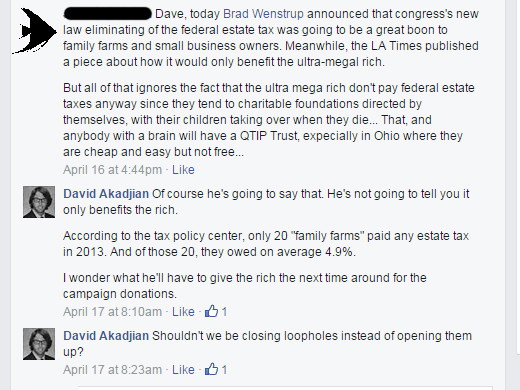

Butterfly never responded back to me. I thought this was a good place to end the conversation. Fish eventually did respond back with a comment that clarified how repealing the estate tax would help the little guy.

This is that argument that the rich are going to avoid paying anyways so why have an estate tax at all.

My first response was to mention how no family farms are affected.

After I wrote it, I realized that what he might be saying is that he’s mad about the loopholes. So I asked, shouldn’t we be closing loopholes instead of opening them?

No response. I thought this was also a good place to end the conversation.

Why do I advocate for a country of leaders?

Because, whether we like it or not, corporate special interest groups have purchased the media. Through their media outlets, they are working very diligently to erase the morals and ideas on which our country was founded.

I believe the way to counter this is to create millions of leaders. We win on issue after issue if we win on ideas (meaning moral values). The inheritance tax is a great opportunity to practice because we have such a strong moral case.

Act and encourage action

Write or call your congress person(s).

Or sign and send the petition to your member of Congress: The estate tax is a vital part of our democracy.

And as always, remember: You. Are Never. Not powerful.

NOTE: If you are in discussions about technical details and specific state and/or federal policies, please note that the estate tax at the federal level is a tax on the total amount of the estate paid by the estate itself. Some states also have estate taxes in addition to those at the federal level. An inheritance tax differs from an estate tax in that the inheritance is treated as taxable income and is paid by the heirs and not the estate itself. Inheritance taxes do not exist at the federal level in the United States, however, they do exist in some states. A decent state by state chart is available here.

—

|

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy. Follow @akadjian |