Alexander Hamilton and the principle of infant industries

Recently, Republican utility regulators in Nevada rolled back incentives for solar energy. One of the big arguments put forward is that these subsidies “distort markets.”

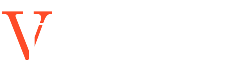

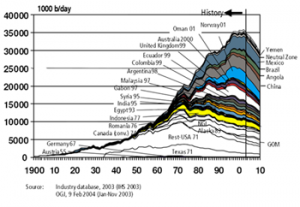

Solar power accounts for roughly 0.7 quadrillion Btus of annual power generation compared to 81 quadrillion Btus of annual power generation from fossil fuels.

In other words, the energy market is already “distorted.” If you think about it, we all know the problem with these distortions. It’s hard to break into a market already dominated by big existing players. Even if something better exists.

Here’s a little bit more about how markets work.

Al Ries and Jack Trout wrote one of the defining books on marketing called Marketing Warfare. If you’re in the marketing industry it’s a little dated, but still relevant as it’s influenced many of the strategies of today.

If you want to get past all the corporate special interest group marketing about the magic of markets and see what corporations really think about how markets work, you can get a good idea from books like Marketing Warfare.

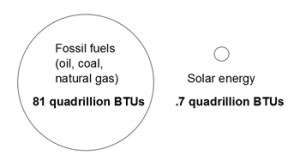

Ries and Trout outline the following strategies based on where you think your company is positioned in the marketplace.

If you are the market leader, you want to stay market leader so they advocate a defensive war. The defensive war should only be played by the actual market leader, not by companies that think they lead in a particular space. One of the principles they advocate is that strong competitive moves should always be blocked.

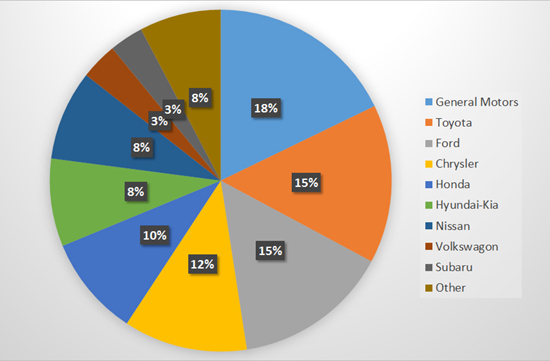

“Free” market theory will tell you that the market leader is always the company with the most superior product. This is bullshit. The market leader is the company that has the largest share of the market. Quite often it has very little to do with whether the product is superior. General Motors was one of the early examples of such a company. Competitors often produced better products, but it wasn’t until relatively recently that they were surpassed in the world market by Toyota and more recently Volkswagon. GM is still the market leader in the United States.

Microsoft is another great example of a company that makes a notoriously mediocre product but is still the market leader in operating systems.

#2 and #3 companies can play offense and try to take over the lead in the market. It is the “height of folly” for smaller companies, however, to try to mount a sustained attack on the market leader. These companies, Ries and Trout believed, simply don’t have the resources to take over the #1 spot.

For this reason, they advise smaller companies to either look to niche markets (try to find an area of the market that is unoccupied). A good example is when Miller Brewing Company flanked the market by developing a light beer, Miller Lite. The category hadn’t existed up until that point. Miller became the instant market leader. Another type of flanking move is what’s called by Christensen and others a disruptive innovation. A good example of a disruptive innovation is the digital camera – today the digital camera has reduced traditional photography to almost hobby/niche status where it used to dominate the market.

Another strategy for smaller companies is called guerilla warfare. In guerilla warfare, the goal is to find a small piece of the market that you can win. The most typical example of this is geography. McDonald’s may be the market leader in fast food. But there are many examples of fast food chains that prosper in a region or that lead in a small segment of the market.

What Ries and Trout understand, however, is that markets naturally distort. There are winners and there are losers and it often has nothing to do with whether a company builds the best widget. Often, it simply has to do with who got there first and is the current biggest:

It’s far easier to stay on top than to get there. The leader, the king of the hill, can take advantage of the principle of force. The law of the jungle. The big fish eat the small fish. The big company beats the small company.

Big companies often beat small companies simply through force and stifling competition.

There is plenty of “force” in markets (though we usually only hear the word “force” in reference to governments).

Alexander Hamilton and the principle of infant industries

One of our founding fathers understood these principles of size and markets. Alexander Hamilton, founder of the treasury, believed firmly in government’s role in helping infant industries until they are able to face up to the force of the biggest and largest players.

There were people in his day who argued that industry, left unto itself, would be sufficient to serve the interests of the community.

In his Report on Manufactures, Hamilton cited three reasons why he thought this was nonsense.

- “The fear of want of success in untried enterprises.” – This means that businesses are inherently risk averse and fearful of something that hasn’t been tried before.

- “The intrinsic difficulties incident to first essays towards a competition with those who have previously attained to perfection in the business to be attempted.” – This is the difficulty of toppling a market leader that Ries and Trout spoke about.

- “The bounties premiums and other artificial encouragements, with which foreign nations second the exertions of their own Citizens in the branches, in which they are to be rivalled.” – This means that other countries often subsidize and otherwise support their own industries.

Hamilton proposed the principle of infant industries:

The spontaneous transition to new pursuits, in a community long habituated to different ones, may be expected to be attended with proportionably greater difficulty. When former occupations ceased to yield a profit adequate to the subsistence of their followers, or when there was an absolute deficiency of employment in them, owing to the superabundance of hands, changes would ensue; but these changes would be likely to be more tardy than might consist with the interest either of individuals or of the Society. In many cases they would not happen, while a bare support could be ensured by an adherence to ancient courses; though a resort to a more profitable employment might be practicable. To produce the desireable changes, as early as may be expedient, may therefore require the incitement and patronage of government.

To translate:

- Markets are slow to change because of established interests and aversion to risk.

- If something is going to be in the public good, we’d be wise to encourage it through government.

Here’s some examples of countries developing infant industries

-

The wool industry in Britain (1700s): Robert Walpole, the first British Prime Minister, protected an infant wool industry with tariffs, subsidies, and other supports. It soon provided Britain enough export earnings to help launch the industrial revolution.

- Manufacturing in the United States (1830s-1920s): During this period, competition laws were severely limited allowing cartels and monopolies to grow unchecked. The U.S. also prohibited foreigners from presiding on corporate boards and disallowed foreign shareholders voting rights unless they resided in the country. Average industrial tariffs were also some of the highest in the world at 40-55%.

- The automobile industry in Japan (1960s-1980s): With the help of the United States and reconstruction funding, Japan heavily subsidized a fledgling auto industry. Today, Japanese cars are considered some of the finest in the world.

- The space program in the United States (1950s-60s): Much of today’s technology came out of research and development that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) developed during the 1950s and 1960s. A few inventions from the space program that we take for granted today include: freeze-dried food, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), memory foam, smoke detectors, solar energy, highway-safety grooving, joysticks, and CAT scans.

In 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, Economist Ha-Joon Chang uses the analogy of sending kids to school to bring home the point that protectionism is often the only way to get infant industries off the ground:

For the same reason we send our children to school rather than making them compete with adults in the labor market, developing countries need to protect and nurture their producers before they acquire the capabilities to compete in the world unassisted.

The fossil fuel industry wants to prevent alternative energy

So what does this have to do with solar energy or alternative energy for that matter?

Quite simply, the oil and fossil fuel industries are going to try to prevent it. We know this because … they’ve tried to prevent it.

They funded corporate special interest groups like The American Petroleum Institute. This is a corporate lobbying group that spent $60 million on government lobbying in 2008-2015.

They funded corporate special interest groups like The American Petroleum Institute. This is a corporate lobbying group that spent $60 million on government lobbying in 2008-2015.

Here is the American Petroleum Institute speaking about climate change in 1998:

Unless “climate change” becomes a non-issue, meaning that the Kyoto proposal is defeated and there are no further initiatives to thwart the threat of climate change, there may be no moment when we can declare victory for our efforts.

In other words, the oil and fossil fuel companies are going to actively work against any efforts to address climate change because they feel it’s going to hurt their profits.

These companies could be investing in alternative energy and trying to remake themselves as alternative energy companies. But, following Hamilton’s 2nd principle that businesses are risk averse, they’d much rather spend money to try and thwart any efforts at alternative energy.

The corporate special interest group marketing goes something like this: “Well, the government shouldn’t interfere and we should wait until technology is cheaper and these things develop naturally.”

Corporate special interests say this because they know that without subsidies, it’s very difficult to get to a point where you can achieve economies of scale. This is a fancy way of saying, technology tends to be expensive when it’s first being developed. Think of the first DVD players. Or the first flat screen TVs.

Subsidizing alternative energy helps grow the market to the point where it can compete on cost with fossil fuels.

Similarly, subsidizing wind power has helped bring down the cost of energy from wind. Jonathan Mir, head of power and utility research for Lazard, says the cost of wind power has come down from $135/megawatt hour in 2009 to $30/megawatt hour today.

A few rules on nurturing markets

There are certain situations where it makes sense for we, the people, to be involved in developing new markets.

When we should nurture markets:

- When there is a significant public good benefit

- When technology is new and hasn’t developed the ability to scale

- When established players are going to work to defeat new technologies

When subsidies don’t make sense:

- For established, profitable market leaders

- For monopolies

- For companies not serving the public good

What’s the benefit of alternative energy?

-

Oil and fossil fuels are finite. It’s not a question of if they will run out, but when. Every prediction I’ve seen says it will happen this century.

- Energy independence. We can produce our energy instead of having to buy it from foreign countries.

- No air pollution.

- Slowing the effects of climate change.

- It is the future. We can either change and adapt and lead. Or fall behind.

I don’t know anyone who isn’t for alternative energy for one reason or another. The only argument I ever hear against it is … well, we shouldn’t subsidize it.

Unfortunately, the current strategy of the fossil fuel industries to kill alternative energy is to prevent protections. We see this with efforts in states like Nevada where the oil-industry has elected regulators to the state utility board. These regulators recently voted to cut economic incentives for installing solar panels. In states like Ohio, we see fossil-fuel backed regulators steering millions into subsidies for coal-fired power plantsand putting state programs for alternative energy on hold.

And if we’re dependent on oil, guess what? Groups like the API have done their job.

I believe we should be working to subsidize and promote alternative energy as an infant industry until the time when it can stand on its own in the marketplace.

Cross posted at Daily Kos.

—

|

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy. Follow @akadjian |