No room for failure: How student debt impacts results

I was lucky: I managed to get through college with only a small amount of debt.

I was able to do this because I was fortunate enough to have middle-class parents, I attended a state school, I received scholarship help, and I got into a co-op program that helped me cover some of the costs.

At the time, I didn’t realize what this would allow me to do. I didn’t realize that it would allow me to take some risks I would never have been able to otherwise.

It allowed me to fail. Not just once, but numerous times. And failure, believe it or not, is critical to success.

This is why I want to talk about how student debt levels today are not only hurting students and recent graduates, but are hurting our businesses—and our country.

Is the world too complex for people to predict global events?

Philip Tetlock asked this question in his 2005 book Expert Political Judgment. Tetlock looked at expert opinions from 1984 to 2003 and quantified how well their forecasts turned out compared to amateurs. Three hundred experts submitted more than 28,000 specific, quantifiable predictions about the future. Tetlock then followed the predictions to see if they came true.

Tetlock came to some startling conclusions. First, experts performed better than random chance—but only marginally better. And second, what mattered more was not what they thought, but how they thought.

The problem is not the experts. It is the complexity of the world we live in.

Paul Ormerod, a British economist, compared the extinction model of dinosaurs to that of businesses. He found that, although the timelines were different, extinction patterns were similar. He also found that when he modeled corporations as successful planners, he wasn’t able to duplicate what happened to businesses in real life. Patterns of extinction were completely different in models that viewed corporations as successful planners.

What Ormerod’s models imply is that there is little correlation between a firm’s amount of planning and its success. What both Tetlock’s and Ormerod’s results suggest is that in these situations where the future is largely unknown, trial and error—and the ability to learn from experience—is essential.

Two of the more famous examples of this are The Beatles and the Apple computer.

Malcolm Gladwell famously wrote in Outliers: The Story of Success that it takes 10,000 hours of practice (or experience) to achieve mastery at something. When The Beatles went to Hamburg, Germany, between 1960 and 1962, what did they gain out of it? Basically, they found a culture that allowed them to play for 10,000 hours. At one point they were playing eight hours a day.

Here’s John Lennon on playing in Hamburg:

We got better and got more confidence. We couldn’t help it with all the experience playing all night long. It was handy them being foreign. We had to try even harder, put our heart and soul into it, to get ourselves over. In Liverpool, we’d only ever done one-hour sessions, and we just used to do our best numbers, the same ones, at every one. In Hamburg, we had to play for eight hours, so we really had to find a new way of playing.

In other words, they had to fail nightly and be able to keep coming back. Before they went to Hamburg, they were terrible and didn’t know many songs. When they came back from Hamburg, not only had they learned stamina and how to perform, but they’d learned an enormous number of songs.

The resurgence of Apple computer in the late ‘90s and ‘00s also starts with failure. In 1997, Apple was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Most people are familiar with the return of Steve Jobs and the introduction of the iMac computer and how it helped revive Apple. Also critical to this story, though not told as often, is that at the heart of the iMac was a new operating system, Mac OS X. The Mac OS was based on the operating system Steve Jobs had developed at his own company, NeXT Computer.

Jobs founded NeXT Computer after leaving Apple in 1985. Initially NeXT was both a hardware and software company, building high-end workstations as well as offering a multi-threaded operating system based on the UNIX platform. By the early 1990s NeXT had become a software-only company. Their NeXTSTEP flagship product was a combination operating system and object-oriented rapid development environment.

Apple, before Jobs’ return, had tried to develop a next-generation operating system. Several high-profile attempts in the 1990s were abandoned. Jobs’ return and subsequent purchase of NeXT allowed Apple to take NeXTSTEP (then called OPENSTEP) and turn it into the heart of Apple computers: OS X.

In 2007, OS X was adapted for a product called the iPhone (iOS). What OS X did was allow Apple to become primarily a software company. This may sound strange for a company known for iMacs, the iPod, the iPhone, and the iPad. OS X allowed Apple to move into and then later dominate the transition of computers from computing devices to digital media devices.

Similar to the success of The Beatles, the resurgence of Apple was made possible because Steve Jobs had spent 10+ years developing operating systems and software with NeXT.

Myriad other examples of success tell a similar story. Bill Gates spent countless hours learning programming in the 1970s before developing DOS, the first Microsoft operating system. Ed Catmull recently talked about how Pixar became so good at developing animated movies:

Well, here’s the thing that we learned. And that is the first versions of all of our films suck. And it’s—and I don’t mean this in a self-deprecating way or that I’m being modest. What I mean is that they all suck. All right? They don’t work.

Catmull realized that the key to great movies was not looking for ideas to turn into films. The key was building teams that were going to be able to solve problems because there were almost always going to be issues with the script. Poet Robert Frost described this as the road “less traveled.”

Silicon Valley creates so many successful companies because they have a culture that allows businesses to fail long enough to become successful. Similarly, in Renaissance Italy, the Medicis created a culture where they nurtured artists and thinkers such as Michaelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci until they could succeed.

Roger Connors and Tom Smith, in their best-selling business book Change the Culture, Change the Game, describe how organizational culture determines results. They demonstrate this relationship through a results pyramid that looks like the one at right.

The way to interpret this is that experiences lead to beliefs which then lead to actions that then determine results. There is also a feedback loop here that’s not described but we see in stories about The Beatles and Apple Computer. The feedback loop says that results then become experiences.

Connors and Smith draw this as a pyramid for a specific purpose. They do this because they say what companies all too often focus on is actions. What do you do when something isn’t working? Try another process.

In other words, the pyramid is like an iceberg. We can see the top and because we can see it, this is often what we focus on.

Connors and Smith argue that if you want to be truly successful, you need to change the culture. In other words to be really successful, we should be focusing on the culture, the experiences and beliefs.

Iceberg captured by NOAA ship Fairweather in 2012. The largest part of the iceberg is beneath the surface.

All that great music from the 1960s and 1970s that we like to attribute to individual talent? It was the result of a culture that allowed people to be able to practice for 10,000 hours. In the 1960s and 1970s, a culture existed that allowed kids to survive and find ways to be able to practice for long enough to master the art of music.

Culture determines results.

How does this relate to education and debt?

Our culture is making it harder and harder for students to fail and succeed by loading them up with debt.

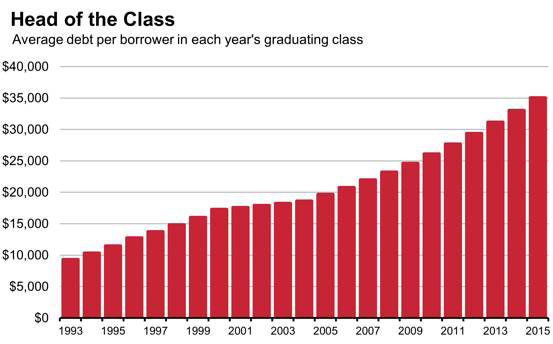

According to the Wall Street Journal, the graduating class of 2015 had the distinction of being the most indebted ever, taking over from 2014, taking over from 2013, and likely to lose to 2016.

The average debt per borrower is a little over $35K. Adjusted for inflation, this is more than twice the debt students had to repay just 20 years earlier. Seven out of 10 of students receiving a bachelor’s degree take out a student loan. Twenty years ago, this number was less than 50 percent.

Student loan debt has surpassed both credit card and auto loan debt.

To deal with this student loan debt, kids have to work longer hours to make the same amount of money that their parents did.

When you load kids up with debt and they can’t make money easily to repay it, they no longer have the ability to try different things. They no longer have the ability to fail long enough to succeed.

B-b-b-but … free?

Free college is now being talked about for the first time and this is a good thing. What I hear in my ear though is the objection, “How are we going to pay for it?”

Here’s how we paid for it before. In the past, people made enough money that they could afford to send their kids to college. This was largely an accident of history. Our economic system was so inefficient that people could make good money.

Today, technology and competition have made our system more efficient. As our economic system has become more efficient, the cost of labor has come down and the inefficiencies have been wrung out of the system.

Unfortunately, these inefficiencies allowed us in the past to create more opportunity.

So we have a couple options: 1) We could put the inefficiencies back into the system to allow people to earn more, or 2) we could simply make college free.

Unfortunately, this idea of making college free is going to offend the older generation, the generation that romanticizes how hard they worked for their opportunities. We’ve all heard the stories. They had to walk to school, seven miles, uphill both ways, typically through blinding snow or driving rain.

It’s a well-worn joke, but we all like to think that our success is because of our individual efforts.

The real reason for our success was largely an accident of an inefficient economic system that allowed many people to benefit. As our economic system becomes more efficient, less and less opportunity is available to our children.

We should all be benefiting from the efficiency gained. Remember the promise of technology: ?That it would make all our lives better?

Instead, what’s happening is that it’s making a few people’s lives a great deal better and it’s reducing opportunity for everyone else.

We’re destroying the culture that allowed us to create great things.

Malcom Gladwell describes the lesson we should learn:

We look at the young Bill Gates and marvel that our world allowed that thirteen-year-old to become a fabulously successful entrepreneur. But that’s the wrong lesson. Our world only allowed one thirteen-year-old unlimited access to a timesharing terminal in 1968. If a million teenagers had been given the same opportunity, how many more Microsofts would we have today? To build a better world we need to replace the patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages that today determine success—the fortunate birth dates and the happy accidents of history—with a society that provides opportunities for all.

There’s a price to pay if we don’t create a culture where people can innovate and create new things. Our next generation isn’t free to fail if it starts out buried in debt.

To do great things, we need a great culture. We need a culture that allows people to fail. If college were free for everyone, it would allow our kids to fail until they’re able to gain enough experience to succeed.

Cross posted at Daily Kos.

—

|

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy. Follow @akadjian |