The cultural revolution you’ve probably never heard of

In the 1990s and early 2000s something happened in the software development world, something that wasn’t good. Software development fell victim to the bean counters and micromanagers of the world and followed a project management script known as the “waterfall method.” The waterfall method was fine for projects that were simple and well-defined, but many many software projects fell out of this realm with either changing requirements, or trying to understand new technology—or sometimes both at the same time.

As a result, many software development projects in the ‘90s were organizational nightmares. Much of the purpose of developing software to begin with (i.e., why are we building this?) was lost as organizations devolved into procedural nightmares and territory fights.

This is the short story of the agile revolution—a term you may have heard of. But you probably didn’t realize was a cultural revolution.

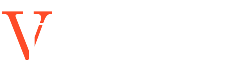

The waterfall method of development looks like the following diagram:

Requirements are written, then the software is “designed,” then it’s coded, then tested, and then it goes into a maintenance cycle.

As software grew in scope, different teams evolved to focus on different stages of this cycle. The people who designed the software were often different from the people who coded the software. As were the people who tested the software. As were the people who spoke with the customer and wrote the requirements. And where does the customer fit in?

What tended to happen was that the customer often didn’t know all the requirements at the beginning of the project, so projects could get stuck in this phase for long periods of time, and/or as requirements were passed to designers and then to programmers, they lost something in translation or new things came up.

What this process often looked like was a long development cycle with very little to show for it at the end. If something wasn’t going to work, you didn’t know about it until a year later and $2 million down the toilet. We used to have a standard joke at one of the places I worked at: If you went to IT, regardless of what you wanted, they would tell you it was going to take six months and cost $1 million. No joke—I received this quote for a website I built myself over a weekend as a mockup.

Graphed out, it looks like the following:

Value delivered over time in “waterfall” development—everything is delivered at the end and the risk of failure grows with time.

You don’t see any results (or value) until the end of the process and it takes a long time. The risk of failure is also highest at the end of the process. Basically, this means that the chance nothing works and you’ve blown through a lot of money with nothing in return is very high.

What was the problem?

A daily agile “sprint” meeting in Denmark. Imagine, designers and programmers and customer account managers all talking to each other! (modified from Klean Denmark/Wikimedia)

It’s tempting to think that the problem was the process—and there’s a bit of truth here. The real problem though was the culture of micromanagement that developed around trying to create organizations to “manage” the waterfall process. The thinking, at the time, was that if we could just nail down this process correctly, everything would be great and work like a machine.

The problem was the beliefs people held.

They valued processes and tools. They viewed complex development in the same way as a manufacturing line. And they forgot about the customer and what the customer was looking for.

The agile manifesto

How did things change?

In 2001, a group of software developers met at a retreat in Utah to talk about lightweight development methods. At this conference they wrote a manifesto—yes, a manifesto—about the cultural change that needed to take place.

The manifesto is simple and looks like this:

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.

Through this work we have come to value:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

There are 12 associated principles of agile software development as well, but the above is their vision statement.

Literally, they stated four key beliefs that ran counter to much of the thinking of the day (and even some thinking that still persists today). They valued individuals and interactions over process and tools, working software over endless documentation, collaborating with customers, and responding to change over some hardened set of never-changing requirements.

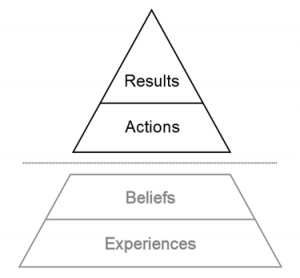

The results pyramid of of Roger Connors and Tom Smith as described in their book “Change the Culture, Change the Game.”

They realized that they needed to change ingrained beliefs and culture in order to see a difference in results. Though many people still think agile is about changing process, it’s really about changing the culture to one that understands complex development and how it works.

The easiest way to think about this is that what we tend to see day-to-day is shaped by what we don’t see—our experiences and beliefs. If you simply change a process, you often don’t really change core beliefs that can lead to terrible results. For example, if people on the team and especially leadership positions value processes and tools over people working together, no process or tool is likely to have much of an impact.

One of the results of agile change is that development changes to a more incremental plan: Let’s see if we can get the customer something in a couple weeks to show, and then let’s build on this value. Subsequently, as a result of thinking about how to deliver value incrementally, risk decreases over time (and you tend to know quickly if something is going to fail).

Incremental “agile” development — value is delivered in small increments and the risk of failure decreases with time. If you’re going to fail, you find out quickly at something small.

Wrap

As we think and talk about revolution, think about the agile manifesto. Think about agile groups like Occupy Wall Street that worked toward cultural change. Ignore the cries to “have an ask”—these are attempts to shift the conversation to the top of the pyramid rather than change bad ideas.

And think about what we want to value. Do we value people more than tools or processes, or even profit? Do we value living in silos and fighting with each other over every crumb, or do we all gain something from working with each other? Do we value individual power or do we value all of our voices? Do we value hierarchical rule or do we value democracy?

Again, remember this doesn’t mean any one thing is worthless. It’s just to say we value one more than the other.

The agile manifesto has led to a revolution in the software industry. It also gives hope for reviving democracy and restoring some of the values I fear we’re losing.

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy (ebook now available). Cross posted at Daily Kos.