‘Boldly Bankrupt’ at the University of Cincinnati: How privatization corrupts public universities

We know there is a crisis in higher education. We see the symptoms in higher tuition, lower graduation rates, and record student loan debt. Too often, the narrative about what’s causing these problems is the idea that these universities just aren’t being run similarly enough to private businesses. Is this true, though? We’ve been cutting funding and pushing privatization on our public universities for 30 years now. What are the results?

The University of Cincinnati (UC) is Ohio’s second-largest four-year public university, withan enrollment of 46,388 in 2019. It has an annual budget of more than $1 billion per year and an endowment of $1.38 billion, ranking it 77th of 818 institutions in the United States and Canada. The school just completed a new $120 million building for its business school.

Recently, a coalition of university students launched a project that looks at the ways in which the University of Cincinnati is being run like a private university. Called “Boldly Bankrupt” (a play on UC’s Boldly Bearcat marketing campaign), the coalition shows who’s benefiting (management, administrators, athletics programs) and who is being hurt most by these practices (students and faculty).

Noemi Leibman, one of the authors behind Boldly Bankrupt and a second-year political science/English double major, told me: “While Boldly Bankrupt was meant to expose these problems at UC, it is also important to realize that these issues exist at a majority of universities.”

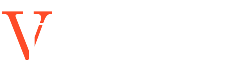

To provide a little bit of background and context, a 2019 study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) showed that compared to 2008, average state spending on higher education is down 13%, or roughly $1,220 per student/year in 2018. The CBPP writes: “Nearly every state has shifted costs to students over the last 25 years — with the most drastic shift occurring since the onset of the recession.”

Source: CBPP analysis using College Board Trends in College Pricing Report and BLS CPI-U-RS

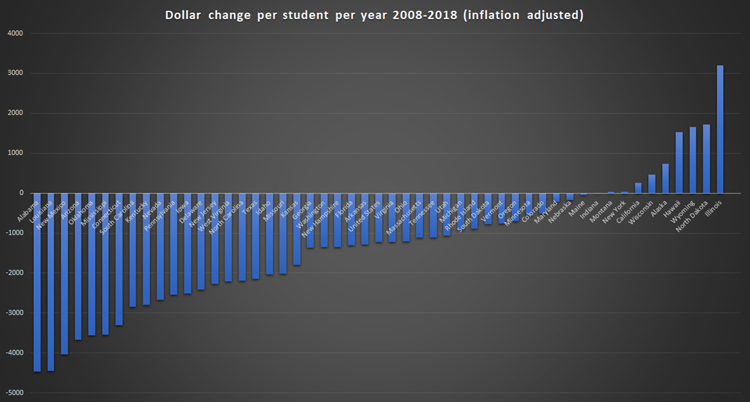

To offset drops in state funding and increases in costs, public universities have raised tuition. Since the 2008 school year, the average tuition at a public university has risen by 37%, or roughly $2,708 per student per year. In seven states, average tuition has increased by more than 60%; 21 states have increased tuition by more than 40%.

Source: CBPP analysis using College Board Trends in College Pricing Report and BLS CPI-U-RS

Why are we seeing so many cuts to funding and increases in tuition? Chicago School economists such as Milton Friedman have argued that competition and market forces should be introduced into public universities in order to reduce costs and provide better education. As states have faced increased costs from pensions and health care, they’ve gradually been adopting this position and reducing public funding to higher education, pushing institutions to find new revenue streams and cut costs.

If this is the case, though, shouldn’t tuition be falling or at least remaining flat? Are we seeing increased revenue streams from the private sector? Are costs falling? What kind of effects are we seeing on education?

In The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them, Christopher Newfield argues that “Today’s problems do not reflect a failure to introduce market thinking but the effects of its long-term presence.”

Newfield demonstrates that introducing market forces actually sets up a race-to-the-bottom cycle that shifts resources away from education, while simultaneously raising costs. This happens in a variety of different fashions. Resources are shifted to revenue-generating activities like athletics; undergraduate programs are used as cash cows to fund graduate programs and research that increase university rankings; the adjunctification of staff continues; and it’s all rounded out with the introduction of cheaper, less effective online educational models, along with consolidation and administrative bloat.

As Peter Odom, a third-year civil engineering student who worked on Boldly Bankrupt, describes it:

Over our time at UC, we have observed a very clear discrepancy between what the University has promised and how it presents itself to the public versus how it actually functions. I think all students notice it to some extent. When you constantly hear about how this or that program is one of the top in the country, and then you turn around to see the crumbling buildings, the inadequate facilities, and the miserable staff, you start to realize that something doesn’t fully add up.

The numbers at UC confirm Newfield’s thesis: privatization is leading to higher costs and poor performance.

Adjunctification

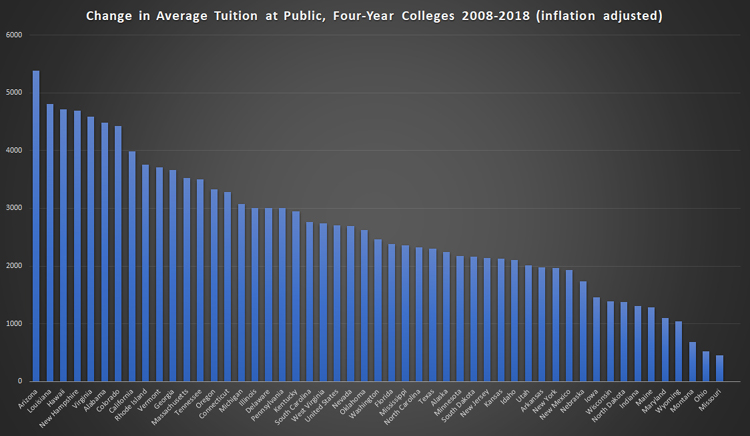

In the 1960s and ‘70s, the majority of professors at public universities were full-time employees who were either tenured or on track for tenure. In 1969, these full-time professorships accounted for 78% of university faculty. Part-time and non-tenure track faculty, often referred to as adjunct professors, accounted for only 22% of faculty positions. The majority of students were taught by full-time professors.

Increasingly, universities have been shifting their workforce away from full-time professorships, which offer higher salaries and better benefits, in favor of adjuncts. Roughly half of the nation’s higher education faculty are adjuncts, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. This rises to two-thirds if other non-tenured positions are considered. In this adjunct model, students may only take a course from a full-time instructor once per semester, or only in upper-level courses.

Universities tend to pay adjuncts somewhere between $2,000 to $6,000+ per course. A full course load is considered to be three classes per semester. This translates to $12,000-$36,000 per year. By comparison, according to the most recent AAUP survey, the average salary for full professors at public universities is $105,644. Associate professors average $82,093 and assistant professors $71,210.

More than 60% of adjunct faculty report having to take one or more additional jobs to make ends meet. According to research from the University of California, Berkeley, 25% of adjuncts are enrolled in public assistance programs.

At the University of Cincinnati, adjunct faculty have increased steadily since the late 1990s.

Adjuncts at UC generally have the same teaching responsibilities as full-time professors. Adjuncts with annual contracts are offered medical insurance, but it’s expensive—and they don’t receive dental, vision, or life insurance. At the College of Arts and Sciences, adjunct faculty haven’t received a raise since 2003.

All of this is happening during a period of extended growth. In the fall of 2008, UC had 37,000 students. 2019 marked its seventh straight year of hitting record numbers, with enrollment in 2019 standing at 46,388.

Resource Shifting

Boldly Bankrupt also highlights some of the resource shifting described in The Great Mistake. Resource shifts occur and cause tuition hikes because of “the large need for institutional funds created by high-status activities that lose money for the institution.” In order to keep their status, universities invest in money-losing activities, like research and athletics. While these activities increase institutional rankings, they also often lose money.

For example, according to Newfield, public universities lose 24 cents on every dollar invested in research. In Division I college football, 12 public schools used $25 million or more in subsidies from student fees or other university support to help balance the budget in 2017, according to data from USA Today. Rutgers ranked first, requiring $33.1 million in subsidies for its men’s football program.

Noemi Leibman described it this way:

Education is clearly being pushed to the side in favor of short-term investments that will make UC “look good.” Athletics are a big flashy attraction, so the university keeps pumping in money despite the program running a deficit of millions. While education theoretically should be UC’s focus, funding academic programs is a hard sell because immediate returns are difficult to measure. That’s why we are seeing the huge increase in the number of adjunct professors and a shift to online classes.

From 2013-2017, the UC athletics program ran a deficit of $102 million. This translates to roughly $1,200 in subsidies annually from each student’s tuition, up from about $800/year in 2010. Meanwhile, from 2005 to 2015, the school saw a 30% drop in instructional spending, the highest drop of Ohio’s eight largest public universities.

Administrative bloat

The head coaches of the football and men’s basketball teams—and their 16 assistants—received a shared total of $8.76 million in 2017. That’s an average of $486,674 each, according to The News Record.

It’s likely even more than this now, as head football coach Luke Fickell signed a six-year, $13.4 million contract in 2017, for an average of $2.23 million per year.

Mike Bohn, the athletic director who left in December, had an annual salary of $552,040 without bonuses at the time of his departure. John Cunningham, the new athletic director, will only make $475,000 per year. New UC basketball head coach John Brannen will make $1.5 million in 2020. His predecessor, Mick Cronin, was making $2 million per year before he departed for UCLA. In 2017, the average pay for a men’s football or basketball assistant coach was roughly $487,000 per year.

Boldly Bankrupt also highlights some of the top paid executives at UC, including president Neville Pinto at $660,000 per year. In 2019, Pinto gave himself a $50,000 raise after the Board of Trustees voted to raise tuition by 6%.

Newfield notes that cuts at the state level are often covered up by increases to public university tuition. In Ohio, funding has increased slightly, from $2.1 billion in 2013 to $2.3 billion in 2018. Even with the slight increase, state funding remains lower than it was before the Great Recession. According to the CBPP, Ohio spending on public education in 2018 was still 16.9% lower than in 2008.

Impact on Education

How is this impacting education?

Boldly Bankrupt describes a recent survey conducted by the American Association of University Professors at UC, in which over 75% of faculty members found that the current budget model provided insufficient resources to their department. In the same survey, nearly 70% answered that the current budgeting model negatively affected the core academic mission of their department.

The model they’re referring to is what the University of Cincinnati calls performance-based budgeting. Under the performance-based budgeting model, revenue targets are set each year for individual colleges, and colleges receive a larger budget if they exceed revenue targets. For example, at the beginning of the year a target could be set at $6 million for the Engineering College. If the College takes in $7 million, it has exceeded that revenue target and may receive additional funds. If it only takes in $5 million, it’s considered to have lost money. The target isn’t based on what the college is spending compared to incoming revenue: it’s only based on the performance target assigned to the college.

While this might sound reasonable on the surface, there are some unreasonable caveats. For example, even if an individual college generates more revenue than costs, if it is not hitting the performance goal, it is considered to be running a “deficit.” For example, if a college makes $5 million in a given year, but the performance target was $10 million, the college is considered to have a deficit … even if it only cost $4 million to run the college.

These phony deficits are also carried over year to year. In the $10 million example above, if a college misses the target by $5 million in a given year, it would start the next year with a $5 million deficit, even if the performance target is increased in that subsequent year.

When colleges have these “deficits,” they’re forced to make cuts even if they’re profitable when comparing revenue to operating costs. These false deficits carry over from year to year for individual colleges; if a college does generate new revenue, it just goes toward that “debt.” The provost’s office can continue to increase the revenue targets, even if they are unrealistic.

Performance-based budgeting has caused the College of Arts and Sciences to have a total operating budget of $0 for the 2019-20 school year.

Emily Chien, one of the Boldly Bankrupt authors who is also a journalism major, described the effects this way:

The College of Arts and Sciences, the biggest and most profitable school for the university, is living on just about nothing. They’ve been put into so much debt, their operating budget equates to $0 for this school year. Another thing that struck me deeply was that literally thousands of our tuition dollars go directly to athletics. We don’t see a penny of our money actually spent on our education. Both of those findings were completely unacceptable for a university branding itself the way it does.

Under these unrealistic expectations, four deans at the College of Arts and Sciences have resigned in the past six years. Heidi Kloos, associate psychology professor at the university, described one dean’s departure, explaining that “We love Ken Petren … [but] no dean can make it. He was very much liked, and yet he cannot function under this budget model.”

What one change would make the biggest difference?

As a graduate of both the Engineering and Arts and Sciences colleges at UC, I was particularly interested in how we could swing the focus back toward students and education. So I asked the above question of the Boldly Bankrupt team. Their answers are below.

Noemi Leibman:

Clearly, the university wants to attract more students. However, instead of long-term investment in academics to make our programs nationally recognized, the Board of Trustees and other administrators choose instead to focus on short-term solutions. This needs to change. Students need to be seen as more than just their tuition money.

Peter Odom:

The biggest change that I can think of would be to create an official yet independent body of student power at the university, like a Students’ Union of some kind. We currently have a student government, but they don’t have any real power to influence the way the administration functions. A democratically run union would allow the entire student body to coordinate and act as a unified force to protect and ensure the rights and voices of the students, and act as a check to the absolute power of the administration. It would be official in that it would be an institution of the university, but independent in that it would be run by and for students, outside of the influence of the administration. Get involved! Meaningful change will only come through the active and democratic will of the student body.

Emily Chien:

The Board of Trustees is not at all a democratic body. Each is appointed by the governor, who happens to be a conservative with little stake in how our university actually functions. Last year, we garnered over a thousand signatures opposing a proposed 6% tuition hike that was unanimously approved by the board despite all of our efforts and support across party lines. Students and faculty must have a say!

Boldly Bankrupt was produced by Fossil Free UC, the Roosevelt Network, the Young Democratic Socialists, the Sustainable Fashion Initiative, and Sustainable Industrial Design. For more information, check out their work atBoldlyBankrupt.com. You can also follow UC Young Democratic Socialists (UC YDSA) onInstagram andTwitter.