Top tip for talking about the economy: Use the active voice

Do you need to be an economist to talk about the economy?

Sometimes I think we think that. “We” being people and “that” being “a Ph.D. in economics is needed.”

If we cede the economic conversation to corporate special interests, however, we lose on issue after issue to the laissez-faire economic story: “Let the markets work.”

At the “Pope is Dope” messaging session this year at Netroots, the panel was asked: What is the biggest mistake people make in conversations?

Without hesitation, Anat Shenker-Osorio responded: “Overuse of the passive voice.”

“People do things,” she said, “If you don’t make it sound like it’s people caused, it is cognitively impossible for it to be people fixed.”

I finally had a chance to read her book Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense About the Economy and I thought I’d share some examples of why this is so important when it comes to the economy.

Let’s start by looking at a standard article from a business paper about the economy. Business Insider recently published this piece from The Economist: The U.S. Economy has reached a turning point.

Starting with the title, I have questions. An economy is not a person or a vehicle and does not drive. If the economy is “turning,” it is because people have made decisions or something has happened that “turned” the economy. I’ll set this aside for a second though as maybe, just maybe these questions are answered in the article.

Here’s what the article goes on to tell us:

- We should expect “higher wages as unemployment falls below 6%”

- There will be “an expansion in consumer credit as households reach the end of the debt deleveraging cycle.”

- The economy grew by 4.6%, matching the fastest quarterly growth rate since 2006.

- “Growth was boosted by improvements across all sectors.”

- “More than 70% of the population think the economy is still in a recession.”

- “The economy is driven, for the most part, by consumers – private consumption accounts for almost 70% of GDP.

- Household debt exploded when the housing market crashed and Americans have “spent much of the past six years reducing debt to a more manageable level.”

- “The debt deleveraging cycle is coming to a close.”

- “The second key trend is in the labor market: the unemployment rate fell to 6.1% in August and the U.S. is on track for its best year of job creation since 1999.”

- “There are also several other forces lining up to support US growth.”

Jesus.

No wonder people feel helpless. The Economist paints the economy like a natural force instead of something people create. We must simply wait and “forces” will line up to support US growth.

What’s missing from this article?

The people and the decisions behind these statistics. For the purposes of comparison, here’s a slightly different story of the financial collapse and the ensuing recovery.

The pyramid scheme collapses

In 1998, Citicorp, a commercial bank holding company, merged with the insurance company Travelers Group to form the conglomerate Citigroup, a company combining banking, securities, and insurance services. Because the merger was a violation of the Glass-Steagall Act and the Bank Holding Act of 1956, the Federal Reserve granted Citigroup a waiver.

Banking and financial corporations lobbied to repeal Glass-Steagall and less than a year later the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act was passed by a Republican Congress and a Democratic President to remove consumer regulations that prohibited one company from acting as an investment bank, a commercial lending bank, and an insurance company. This legislation failed to give the SEC or any other financial regulatory agency the ability to regulate these mega-financial Wall Street corporations.

Not surprisingly, more mergers followed and banks become both investment and commercial banks.

This crap was sold to us by corporate special interest group marketing that claimed the market would “regulate itself.”

The legislation allowed single companies to make risky investments with FDIC-insured consumer deposits. In other words, there was zero risk for these “too big to fail” companies and only upside. If you made money, you made money. If you didn’t, the government (meaning: we, the people) would foot the bill to protect the consumer deposits.

With interest rates near zero, asset managers started looking for higher return investments. One of the favorite was mortgage-backed securities. These were sold as low risk even though they contained sub-prime loans.

Credit agencies like Moody’s and Fitch gave these junk securities AAA ratings.

No agency existed to regulate derivatives. This allowed companies like AIG to issue $3 trillion in derivatives without any reserves for future claims.

In 2004, the SEC changed the rules for five Wall Street banks granting them exemption from a 1977 law limiting them to a 12 to 1 leverage limit. This allowed unlimited leverage for Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns. These banks upped their leverage to 30 to 1 or 40 to 1 so when things went south, they went south fast.

None of these five banks would have survived without the $700 billion federal bailout.

Now I know I’ve left out much of the story. We could really take this story back to the 1980s when bank deregulation first began and led to the Savings and Loan crisis. I think you get the point though that the economy doesn’t just happen.

Corporations and corporate special interest groups actively worked for an economy that would benefit them. They actively worked to privatize profits and dump the risk on the public. These same groups are the same groups still blaming the government and working to block all attempts at a working economy.

Again, my goal here is not to tell the entire story of the financial pyramid scheme, but to demonstrate what stories about the economy should look like.

Note: More on this story can be found in a fantastic article by Steve Denning at Forbes. As an aside, Steve Denning gets that “people do things” because Steve Denning understands narrative and story like few others having written several books on the subject including The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling.

Returning to The Economist article

Let me now return to The Economist article to fill in some of the details about the economic recovery.

When The Economist says that we’ve reached the end of the debt deleveraging cycle what they mean is: people like you and I have spent the last six years busting our asses to get out of debt because suddenly our house values plummeted.

People lost their homes. People who didn’t lose their homes cut back. Spending stopped. People put any extra money into paying down debt.

In other words, we, the people, bore the brunt of the housing pyramid scheme.

We, the people, “turned” the economy after Wall Street mega banks looted it with the help of their lobbyists.

When The Economist states that people don’t believe we’re in a recovery, what they mean is that it sure the hell doesn’t feel like a recovery because we’re still paying for the actions of the Wall Street mega-financial corporations.

If, as The Economist tells us, the economy is driven, for the most part, by consumers, you have to wonder why we spent so much money bailing out banks.

If “private consumption accounts for almost 70% of GDP,” why are our economic policies still focused on the “supply side”?

Why is our driving economic philosophy still this horrible corporate idea that if we give money to the people at the top it will somehow trickle down?

Why are we told that everyone “needs to tighten our belts” when clearly there are certain people so fat from these schemes that no belt in existence would fit them?

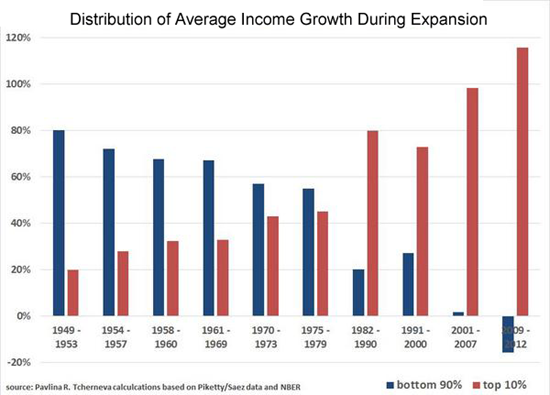

Translating the above graph from Paulina Tcherneva: Why do we give a shit about growth (expansion) if growth only benefits 10% of us?

Presenting all these statistics as if the economy somehow rules over us and we have to just stand back and let its magic wash over us seems clearly ridiculous when we see how corporations actively work to write the rules in their favor.

If we use the passive voice, we reinforce the idea that the economy is a natural thing, not something we created and can create towards whatever end we choose.

Do we really want an economy that works for just a few people? Or do we want one that works for everyone?

As Shenker-Osorio writes:

Right now in the economics realm and beyond, our words convey the message that policies magically change, bad things come to pass, and problems are mysteriously visited upon us.

Or, as John Oliver said: “If you want to do something evil, put it inside of something really boring.”

I could go on. Instead, I’m going to leave you with this tip from Anat:

The polite passive voice we’ve adopted may make us sound reasoned and neutral – like cool-headed experts or academics. But it obscures the truth and lets guilty parties off the hook.

If you’re interested in more about how to talk about the economy, I highly recommend Anat’s book: Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense About the Economy

Cross posted at Daily Kos.

—

|

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy (release scheduled for October).Follow @akadjian |