How to really make America great again: Get rid of ‘the dumbest idea in the world’

One of the best questions you can ask people in organizations that are struggling is:

If you could get rid of one thing, what would it be?

It’s a great question (and also one that should be asked in confidentiality) because:

- It’s hard to think about changing everything.

- It’s easier to think about one thing to eliminate.

- People often have a really good idea about what that one thing is in an organization. Often it’s the elephant in the room that people can’t talk about publicly for fear of retribution. Sometimes, it’s a person.

One thing clearly stands head and shoulders above the rest when you talk to many people in corporate America. It’s an idea that completely removes responsibility from many corporations in our society. It’s an idea that threatens not only our constitutional democracy, but also every value Christians hold dear and every value we hold dear from modernity and post-modernity.

It’s an idea so bad that Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric, called it “the dumbest idea in the world.”

The idea, called shareholder value theory, is that the sole purpose of publicly-held corporations is to return profit to shareholders.

Customers be damned. Society be damned. Families be damned. Results be damned. America be damned.

Ayn Rand was one of the first to hint at such an absolute in The Virtue of Selfishness in 1963. She saw altruism and selfishness as exact opposites. Belief in one precluded belief in the other.

Altruism permits no concept of a self-respecting, self-supporting man — a man who supports his life by his own effort and neither sacrifices himself nor others.

No wonder people like Mike Wallace took Rand for a cult leader in 1959. Not only did she advocate against any and all ideas about the common good—she also insisted that selfishness was the only thing anyone needed.In The Virtue of Selfishness and her other works, Rand argued for selfishness (or profit) as the only moral needed and also held that somehow any acts of altruism were immoral.

The person who really brought the idea front and center, however, was Milton Friedman in a 1971 article in The New York Times titled “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.” Friedman claimed in his article that executives who pursued anything other than pure profits were “unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.”

Friedman saw the market as a machine that we should serve and optimize, rather than as a thing we create to make our lives better.

He also argued that executives should be responsible only to shareholders, and that shareholders want only one thing: Profit.

In a free-enterprise, private-property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.

While critiquing his opposition’s views as lacking intellectual rigor, Friedman’s entire argument is based on a single assumption: That people have no interest other than greed, and that greed will somehow lead to a greater good.

He can’t seem to imagine that shareholders might want a better world. And he can’t seem to imagine how greed might lead to unethical behavior.

Impact on corporations

Steve Denning writes in Forbes about the problems with shareholder value theory.

Here are some of the impacts on corporations:

- Short-termism: Companies become focused on quarterly calls and pumping up short-term profit numbers.

- Dispirited employees and managers who work for little more than money.

- “Bad profits” that can hurt companies in the long run.

- Pursuing extraction of value rather than creation of value. Goldman Sachs, before shareholder value theory, was a completely different company that would often turn down deals if they believed they weren’t in the long-term interests of clients. Today, they would take the deal anyway. Even General Electric, a company once touted as a success of shareholder value theory, has turned away from it because the company gained most of its successes through GE Capital and financial “wizardry.” Much of this collapsed in 2008.

- Constant pressure to keep more of the gains from any worker improvements in productivity.

- Reduced innovation.

- Pursuit of easy gains from financial engineering (sometimes illegally).

Privately held companies, which are free from the pressures of shareholder value theory, invest more and create more value than publicly-held companies. Privately held companies invest 6.8 percent of total assets, compared

with 3.7 percent for publicly-owned companies. Rather than invest, publicly-held companies are more likely to spend money on stock buybacks.

Why? Because once again, their mission is driven solely by short-term profit to shareholders rather than long-term value.

Boeing is another great example of a company that’s fallen victim to shareholder value theory. In Fixing the Game: Bubbles, Crashes, and What Capitalism Can Learn from the NFL, Roger L. Martin, former Dean of the Rotman School of Management, talks about what happened when Boeing tried to maximize value for shareholders:

The CEO behaves, in other words, as Philip Condit, former CEO of Boeing, did. In 2001, in the interest of maximizing shareholder value for his multitude of anonymous owners, Condit essentially put the location of Boeing’s headquarters out to tender. He announced that Boeing would leave its longtime headquarters in Seattle for whichever city could deliver the best package of incentives and credits. Chicago won, offering the biggest municipal bribe (oops, I meant “incentive”). Boeing forsook Seattle, its home for eighty-five years, for an offer from the highest bidder. But even that mercenary move wasn’t enough for the expectations beast. Short-term shareholders kept pressuring Boeing for ever higher earnings increases. In its efforts to satisfy them, Boeing engaged in procurement corruption and industrial espionage, which resulted in huge fines, jail terms, and the forced resignation of Condit (and, in due course, his successor as well).

Chicago paid $63 million.

Does a focus on returning profits to shareholders increase shareholder value?

The short answer is “No.” Exactly the opposite happens.

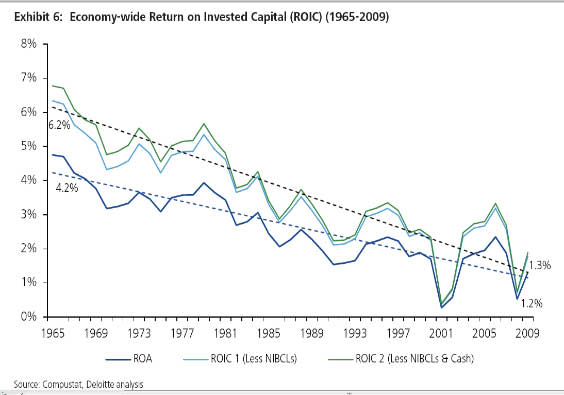

The Shift Index was a study of 20,000 U.S. firms conducted by Deloitte’s Center for the Edge. The idea was to try to get beneath the gossip, marketing, and hyperbole and discover what really drives business performance.

According to the Shift Index, the rate of return on assets and on invested capital of U.S. firms declined from 1965 to 2009 by 75 percent.

Yet from 1980 to 1990, CEO compensation doubled. From 1990 to 2000, it quadrupled.

A great example here is Apple Computer. In 1983, Apple hired John Sculley as its CEO. Formerly, he had been a VP and president of Pepsi-Cola. Sculley kicked out Steve Jobs, one of the founders of Apple.

By 1993, Apple was on the verge of collapse and was worth only $2.1 billion. Sculley didn’t understand the technology market and Apple was on the verge of going out of business. The company was focusing on increasing shareholder value and had forgotten its customers.

Jobs returned in 1997. Within a short span, Apple introduced a new operating system. Then the iPod. Then the iPhone. Then the iPad. By 2010, Apple passed Microsoft to become the largest technology company in the world.

What happened?

Jobs focused on customers and the long-term instead of on “shareholder value.” Jobs had a vision. Sculley had no idea what he was doing.

Ironically, focusing on “shareholder value” destroys shareholder value.

Government capture

I mentioned earlier that “shareholder value” often leads companies to the unethical. Similarly, many companies have found that they can get short-term perks from governments that can temporarily boost stock prices.

Boeing’s move to Chicago was one example. Here in Cincinnati, a health care company called Omnicare recently moved across the river from Covington, Kentucky, for incentives worth $7.3 million. Ohio Gov. John Kasich touts this as part of his success in creating jobs. However, the company moved less than a mile. No “jobs” were created. The company just took advantage of a political situation to secure $7.3 million from a local government. Is paying $7.3 million for a company to move across a river really the best use of public funds?

Today, moves like this are commonplace with companies.

The quest to increase profits for shareholders is increasingly leading to unethical behavior and companies buying influence with government in order to guarantee profits.

We see this with the privatization of schools. We see this with the health care industry blocking government competition that would reduce their profits. We see this with companies like FedEx and UPS lobbying for legislation to cripple or privatize the U.S. Postal Service. We see this with companies fighting for anti-union legislation to reduce worker pay. We see the creation of monopolies like Time Warner Cable and Comcast. We see pensions being raided. We see tax loophole after tax loophole.

We see banks gutting regulations that lead to the collapse of the world economy.

Shareholder value theory has removed all responsibility from corporations, has incentivized unethical behavior, and has created a race to the bottom. In the U.S., it has also put companies at war with people and our democratic government.

All in the name of short-term profit. Not long-term profit. We’ve already seen that in the long-term, shareholder value theory actually decreases shareholder value.

We weren’t always like this

Keep in mind, shareholder value theory is new, dating back to Milton Friedman in 1971.

It didn’t come from our founders. It’s a recent radical remaking of society.

In the American Revolutionary War, we actually fought as much against the monopoly of the British East India Company as we did against the British. It wasn’t just any tea we dumped into Boston Harbor. It was British East India Company tea.

We did this because the British East India Company was responsible for the British government passing the Tea Act of 1773. The reason for this legislation was to allow the East India Company to cheaply dump tea in the colonies and still make a profit and also, simultaneously, to tax the tea.

After America won its independence, we were very wary about any kind of corporate charters and didn’t allow any for nearly 100 years.

When we started chartering corporation again, we did so only for public works projects like railroads. And corporate charters could be revoked if they caused significant harm.

A better idea

Marc Benioff, chairman and CEO of Salesforce, said the following at the World Economic Forum in 2014:

The renowned economist Milton Friedman preached that the business of business is to engage in activities designed to increase profits. He was wrong. The business of business isn’t just about creating profits for shareholders — it’s also about improving the state of the world and driving stakeholder value.

Benioff endorses the stakeholder vision of Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum, in which corporate management should focus on serving the interests of all stakeholders.

Companies like Apple, Johnson & Johnson, Toyota, and Proctor & Gamble create value not by focusing returning profits to shareholders, but by focusing on customers.

Douglas K. Smith, former McKinsey consultant and author of On Value and Values: Thinking Differently About We in and Age of Me, writes about re-integrating values (other profit) back into the corporate world.

He talks about:

- Ethical scorecards

- Annual reports to that focus on what matters to employees of the corporation

- Corporate purchasing for employees

- Bringing democracy and transparency into corporations through

- Jury trials (of peers) within organizations for organizational violations

- Employee oversight of lobbyists

- Customer and employee participation on boards of directors

- Free presses within organizations (very different from a newsletter)

- Minimum values standards for vendors

- Efficient capital markets for non-profits

The goal of all these efforts: Deliver value to everyone.

If we really want to make America great again, let’s get rid of Friedman’s shareholder value theory.

Not only is it destroying corporations, messing up democracy, and wiping out our cultural values in favor of a “profit only” approach—but in the long run, it doesn’t even deliver greater value to shareholders.

Focusing on profits as the only purpose incentivizes companies to cheat, to engage in financial shell games, to cook the books, to invest less, to take their eye off actually delivering value, and to engage in bribing governments. All in the name of short-term profits.

It benefits no one and it’s fundamentally destroying society as we know it.

Let’s replace shareholder value theory with something like Schwab’s stakeholder vision, and let’s reintegrate values and “doing the right thing” back into the corporate world.

If we really want to make America great again, we should reintroduce democracy into publicly-held corporations.

Cross posted at Daily Kos.

—

|

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy. Follow @akadjian |