Democratic capitalism: Freeing people from the corporate special interest definition of ‘corruption’

This week someone asked me if I’d heard any questions about IDEA, the federal law protecting students with disabilities (the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act), during Jeff Sessions’ confirmation hearings.

I get these types of questions a lot because I write about politics. It’s kind of funny because I don’t think I know much about politics—at least not when it comes to policy details. I’ve had people tell me in response, “But I love listening to you talk. You know so much.”

Here’s a secret: It’s more important to know what you believe in—and how to talk about what you believe in.

The problem is that corporate special interests “get” this, and all too often we don’t—especially many of us who come from academic backgrounds, where arguing is the accepted way to flesh out ideas and learn.

Let me demonstrate by showing you how corporate special interests redefined “corruption,” why this is so important, and how you can help break people out of this trap.

My favorite model for how people learn looks like this:

This model basically describes how your culture and experiences determine results. Experiences inform beliefs, values, and principles—which determine actions and lead to results. Ideally, the results we get should then become our experiences and may change some of our beliefs, values, and principles. We “grow” as we try things and our results change who we are (beliefs, values, principles).

In the political world, you can think of policy as what happens toward the top of the pyramid, where we turn granular principles into actions and rules of law.

When we’re talking to people about politics, we often talk at these higher levels about what policy should look like. We assume that people agree with us on our values and beliefs.

If you make this assumption and you disagree on values or beliefs, it’s almost impossible to come to similar conclusions about policy. I’ve heard this referred to as people having different “worldviews.”

Worldviews tends to imply that our beliefs are set in stone. This is silly. Our worldviews change all the time as people have different experiences or learn new things.

Corruption (original meaning)

One of my favorite examples of this is how corporate special interests have changed the meaning of corruption.

In a 1905 address to Congress pushing the federal Corrupt Practices Act, Teddy Roosevelt said:

All contributions by corporations to any political committee or for any political purpose should be forbidden by law; directors should not be permitted to use stockholders’ money for such purposes; and, moreover, a prohibition of this kind would be, as far as it went, an effective method of stopping the evils aimed at in corrupt practices acts. Not only should both the National and the several State Legislatures forbid any officer of a corporation from using the money of the corporation in or about any election, but they should also forbid such use of money in connection with any legislation save by the employment of counsel in public manner for distinctly legal services.

Corruption, to Roosevelt, meant corporations buying government. It meant Senate and Congressional representatives should be responsible to the people they represent. It meant representational democracy.

Corruption redefined by corporate special interests

If you talk to conservatives today, most have a very different belief about corruption. When they say “corruption,” most often they’re thinking something very different from what you’re thinking.

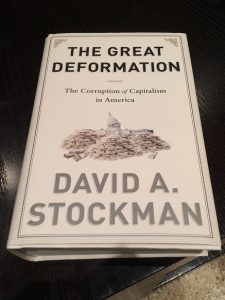

Former Reagan advisor David Stockman illustrates this view in his book The Great Deformation: The Corruption of Capitalism in America.

In Stockman’s opinion, the system we should be “optimizing” is capitalism and his belief is that government corrupts capitalism. It “picks” winners and losers when these winners and losers should be determined by a survival of the fittest, and all problems with capitalism will eventually be fixed by capitalism itself.

Stockman called corruption “crony capitalism.”

When conservatives use this phrase, what they’re referring to is not the buying of government, but government somehow “deforming” capitalism. This is why their policies are designed to separate government from ownership and capitalism.

Much of this thought comes from Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom. Friedman was both a brilliant economist and possibly the best corporate lobbyist ever. Early in his career, the corporate think tank Foundation for Economic Education employed Friedman to write a pamphlet for the real estate industry against rent controls. Capitalism and Freedom is largely a summary of his best lobbying work.

Friedman kicks off Capitalism and Freedom with what we’ve all heard a million times echoed again and again in corporate media:

First, the scope of government must be limited. Its major function must be to protect our freedom both from the enemies outside our gates and from our fellow-citizens: to preserve law and order, to enforce private contracts, to foster competitive markets.

Corporate special interests (especially large ones) loved Friedman because he believed we should privatize most government functions. If you read Friedman closely, his views are actually much more nuanced. In the very same paragraph he wrote about limiting government, for example, he also said:

Beyond this major function, government may enable us at times to accomplish jointly what we would find it more difficult or expensive to accomplish severally.

Similarly, Friedman raises issues of economic inequality in Roofs or Ceilings?. But these issues are largely buried by his case for private ownership (what special interest groups liked about Friedman). Any nuance was lost, the chants to privatize everything were taken up, government was portrayed as “interfering,” and today many on the right even disavow Friedman for mentioning the role of government at all.

These are some of the roots, however, of how corporate special interests redefined corruption as government interference.

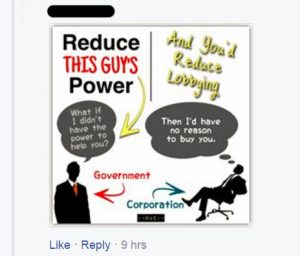

It’s why when you’re talking to conservatives, you’ll see things like the following memes:

And this one:

These are almost Yoda-like in their zen brilliance: Impossible to deconstruct, because they deconstruct themselves.

The problem is that what corporate special interests want is to privatize government. In other words, they’re in a sense saying “If you give in to us (give us education or social security or the military or whatnot) you won’t have to give in to us again.”

Corruption is gone because you’ve given corporate special interests what they want. Basically, what they want is to be their own fiefdoms with no oversight. Yet at the same time, they want government to protect their property and capital and to also build their infrastructure and educate their employees.

Privatize the profit, socialize the risks (or costs).

Swimming upstream against corporate special interest propaganda

Contrary to what many of us typically think, this is some of the most advanced propaganda in the world. We often call it “stupid.”

If you think about it for a second though, corporate special interests started with what they wanted—selling off as much of our country as possible to private owners—and created a philosophy that would make corruption seem reasonable. They used some of the most brilliant minds of the day (such as Friedman) to justify what they wanted.

Those of us who find it “stupid” tend to find it stupid because we hold different underlying beliefs. The problem is that corporate special interests have literally billions to spend disseminating their beliefs and working to turn them into common sense.

This is why it’s so difficult to accomplish progressive goals these days. Because corporate special interests and their think tanks and media are spending so much to make their horrible ideas make sense. We’re swimming upstream against corporate media (as once upon a time corporations viewed their own efforts as swimming upstream against what they started calling “liberal media”).

Democracy

The way to break people out of these bad idea traps is to talk about better beliefs in simple ways that people can understand.

Basically, if you want to make sense when talking about corruption, you need to return corruption to its original meaning; corruption of democracy.

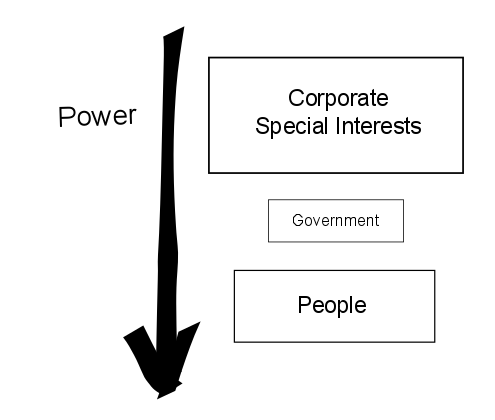

The way I’ve found this works best is through a simple drawing. Start with the problem: Corporate special interests are purchasing government.

What does this look like?

Corporate special interests are at the top of the drawing. People are at the bottom. If you can, ask the person you’re drawing this for if it describes the problem. Does this sound right to you?

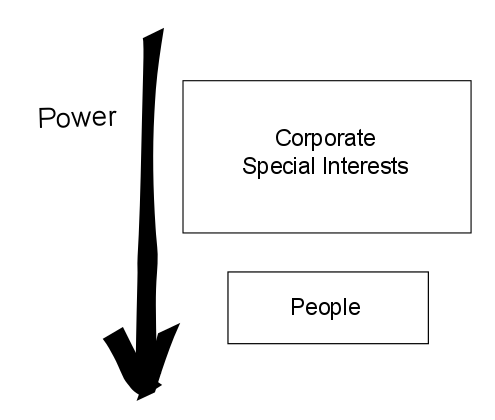

Then, draw the Milton Friedman solution: smaller government.

In this picture government is smaller. But it doesn’t fix the problem. The problem is that people are still at the bottom and corporate special interests are still buying government. And if they’re buying government, they’re actually bigger.

If we eliminate government altogether (as some crackpots argue), we’re then left with rule by corporate special interests.

Suddenly, “smaller government” doesn’t make sense any more.

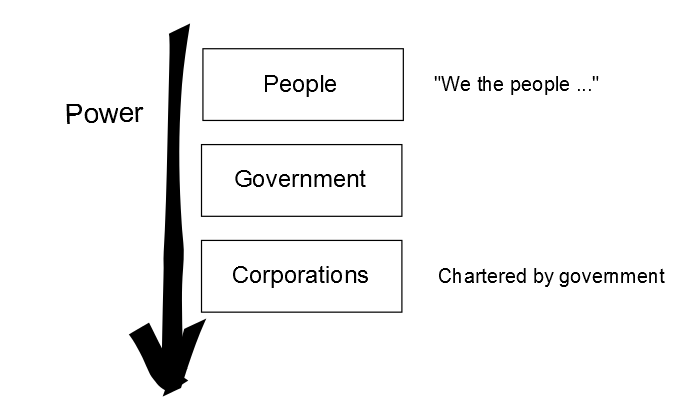

What makes more sense is democracy (as envisioned by our founders).

Both government and corporations should benefit people. In this vision of how things work, the vision of our founders, corporations were only chartered for the public good. In other words, they were chartered to serve people.

We placed strict rules on corporations for 100 years after the Revolutionary War because we fought the war as much against the British East India Company monopoly as we did the British. That tea that was dumped in the harbor, it wasn’t just any tea. It was monopoly tea.

- Some of the limits we established in our fledgling representative democracy were:

- Charters were granted for a limited time and would expire if not periodically renewed.

- Corporations could only engage in activities necessary to fulfill their charter.

- Corporations were often terminated if they exceeded their charter or caused public harm.

- Corporations could not make political or charitable contributions nor spend money to influence law-making.

- Owners and managers were responsible for criminal acts committed on the job.

This is what democratic capitalism looks like.

Another way to say this is:

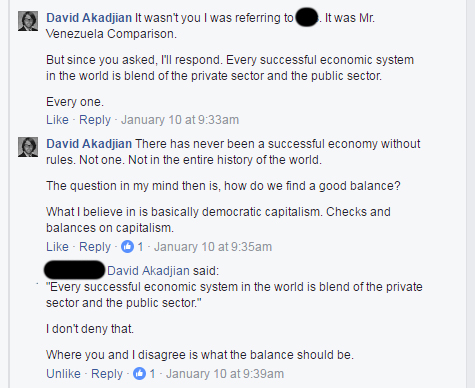

Every successful economy in the world is a mixture of public sector and private sector. Every one. They seem to be most successful when they’re run by and for people.

For practice, I like to hang out in the most conservative places I can find. I know I likely won’t win with many of the believers who’ve been believing since the ‘80s. But they force me to up my game to the point where I make it difficult for them. Even when I’m vastly outnumbered. And more importantly, I’ll win all the independents (who I really want to win).

One of the tricks in their bag is to call me a socialist.

When this happens to people, I often see them get defensive and call them names back because, by and large, most liberals I know aren’t socialists. At least not in the sense of Venezuela. We’re democratic capitalists. We recognize that all capitalism does is set prices on things. It doesn’t solve social problems. It doesn’t care about things like justice or individual rights. Capitalism once put a price on slaves. It didn’t solve slavery, or end child labor, or help women get the right to vote. Democracy did these things.

In the above example, what I’ve done is a couple things.

First, I’ve opened up some mental space. The discussion is not capitalism versus socialism any more. This is the trap. If it’s capitalism versus socialism, we have a very weak argument and they have a very strong one. Not many people believe that complete centralized control over the economy is a great idea. I don’t. Corporate special interests love this fight because it’s easy to win.

Second, I’ve reframed the goal as finding a balance: democratic capitalism.

Since we both agree on the goal, suddenly we’re having a discussion about how to make this work. The discussion isn’t him versus me anymore.

This then allows us to start talking about what this balance should be. What does the private sector do well? Consumer goods, for example. What does the public sector do well? Public services like health care and education.

Most importantly though, he understands my beliefs and why I’m talking about things the way I do. This is critical because many many folks I’ve talked with honestly don’t understand why liberals think the way we do. Their view of our beliefs tends to be much different than our own view (also due to how we’re portrayed in the media).

Within the context of democracy and democratic capitalism, the following policies “make more sense” to people:

- Repealing Citizens United

- A fair and non-partisan election process

- Getting money out of politics

- The Fairness Doctrine

- Voting rights

- Public financing of elections

- Public education

- Regulations and standards for corporations

The trick is that you first have to bust them out of the corporate special interest group frame that pits laissez-faire capitalism against socialism as the only two alternatives.

Here’s the best part: You don’t need to know policy details. What’s more important is knowing what you believe about democracy and capitalism and learning to have conversations at an “I believe …” level instead of a policy level.

And, more importantly, as more and more people start talking about democratic capitalism, it starts to become shorthand in the way “smaller government” became shorthand for conservatives. This is why I recommend people have these conversations about democracy and democratic capitalism as much as possible.

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy (ebook now available). Cross posted at Daily Kos.