The division line exercise and the 99 percent

This is an exercise I picked up from Srdja Popovic, one of the leaders of the Otpor! movement that toppled Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic.

The exercise is simple: You are a leader in a movement to overthrow Milosevic and bring back democracy. You need to unite people.

Draw a line on a sheet of paper. You’re on one side and everyone else is on the other. What will win the most people over to your side?

Let’s take a look at a few examples to see how this plays out.

Occupy Wall Street

In his book Blueprint for Revolution, Popovic writes about both his excitement and his disappointment in the Occupy movement.

Focusing on the latter first and thinking about the division line exercise, he talks about who supported this movement:

Here’s a brief and very incomplete list of stars who supported the movement: Kanye West, Russell Simmons, Alec Baldwin, Susan Sarandon, Deepak Chopra, Yoko Ono, Tim Robbins, Michael Moore, Lupe Fiasco, Mark Ruffalo, Talib Kweli, and Penn Badgley from Gossip Girl. It doesn’t take a cultural critic to realize that these entertainers appeal to a very particular segment of the population,the segment that listens to rap and subscribes to liberal politics and digs highly praised but little-watched cult TV shows like 30 Rock and The Kids are Alright.”

He speaks about how people in rural America, people who were probably experiencing the tyranny of the 1 percent the most, might have felt upon seeing all of these people supporting Occupy.

To them, it probably looked like they didn’t understand what was going on.

“The culture and group identity of Occupy never made itself very inviting to this type of person. Which, if you think about it, would have been very easy to do: all it would have taken—and I’m oversimplifying here, but not by much—is for a few invitations to go out to musicians who weren’t perceived as the usual suspects. What if, for example, instead of Talib Kweli leading the crowd in a rousing rap chant, someone like Lee Greenwood, best known for his song God Bless the U.S.A., showed up and belted out a few patriotic tunes? Anyone watching in the heartland would get the feeling that the movement truly saw itself as a unifying force, not just a liberal outburst but a real attempt at a conversation.”

Democratic socialism

This past election saw something we haven’t heard in a long time: A democratic socialist running for President.

Bernie Sanders’ run was amazing and really spoke to the fact that our country is looking for some new ideas.

Let’s apply the division line test to democratic socialism, though. How many people are going to come over to my side?

There is actually a real world example of this: where Bernie campaigned. He campaigned on college campuses or in cities with a very liberal base.

I live in Ohio. When you say “socialism” here to many folks they look at you like you’re from outer space, even if it’s democratic socialism. This is why Bernie spent so much time having to explain “democratic socialism.”

I love Bernie. I voted for Bernie. His problem, however, as a democratic socialist, is that he again is reaching only a certain audience.

Now … if he were a democratic capitalist his odds of bringing people over to his side suddenly jump (shhh … it’s pretty much the same thing).

The civil rights movement

In thinking about the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, the first two things that come to my mind are that it was a movement about equality and justice.

Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke about his dream in these terms:

I have a dream that my four children will one day be judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

The movement pulled people from outside the black community in because it was a moral movement. It was a movement that spoke to inequality and justice.

And yeah … let’s not romanticize this … things weren’t much different then than they are now. There was a lot of resistance from whites, especially in the South.

But the movement managed to pull enough people over to their side to succeed in passing civil rights legislation. They did this by focusing on three things: non-violence, justice, and equality.

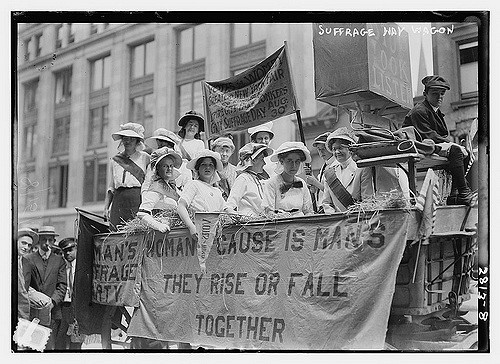

Women’s suffrage

Similarly, the women’s suffrage movement focused on equality and the injustice of nearly half of our population not having the right to vote.

Here’s Susan B. Anthony, pulling people over to her side of the division line:

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men.

Pussy Riot

Let’s compare this for a second to a movement from Russia that has gained notoriety: Pussy Riot.

The movement behind Pussy Riot is similar in many respects to the Occupy movement in terms of who they pulled over to their side. They pulled over the liberal elites of Russia, the college students, the LGBT crowd, the educated.

Here’s Srdja Popovic on Pussy Riot:

“Had you asked any of the marchers in Moscow if they welcomed their cousins from the boondocks into the fray, you probably would have heard impassioned speeches about how important it was that all Russians stand together. But It didn’t happen. It’s not that Muscovites weren’t entirely welcoming of others. … They didn’t go out and listen to people all over the country to figure out how they might be able to bring all sorts of different folks to join their cause. Movements are living things, and unless unity is planned for and worked at, it’s never going to materialize on its own. And that’s why it’s important to make your movement relatable to the widest number of people at all times.”

Amazingly, the recent women’s march in Washington didn’t seem to face this issue—in part because they pulled people in from so many different backgrounds and it wasn’t billed as some kind of march to “End Patriarchy!”

Make America Great Again

Please don’t get me wrong: I hate Donald Trump.

But if you think about his campaign slogan from a division line exercise standpoint, it’s not bad.

Yes it’s a little simple and nationalistic, but he managed to rally enough people to win the presidency in an upset almost no one predicted. We can talk all we want about how he used racism etc, etc. but he reached out enough to other sides to pull people in or to at least prevent people from strongly supporting Hillary Clinton.

Trump and his campaign brought enough people over to his side of the division line to win an election.

Black Lives Matter

We already know the division line answer to this movement because it’s been played by the opposition.

They’re fighting for All Lives Matter.

They clearly don’t mean it. Most of the people I know who say this are people who hate blacks. I know this because I’m white and I can walk into any rural bar in America and people will start talking to me about race the minute they find out I live in the city of Cincinnati.

They don’t like the city because to them, the city means black people

I understand why Black Lives Matter chose their slogan. They chose it because they believe education is the answer and it’s a great conversation starter: “Why do we even need to say Black Lives Matter?”

This is a great effort for teaching the next generation.

Look, though, at how the opposition loves this fight. They will talk about how all lives really matter all day. They put Black Lives Matter on the air all the time. And usually they’ll air footage of looters who aren’t even affiliated with the movement and try to characterize them as BLM activists.

They have been very effective in branding the Democratic Party as a party focused on what they’ll call “the fringe”—and they don’t just do this with race. They do it by talking about any and all of the extreme activists on what they call the “liberal left.”

I support BLM and the BLM movement.

If, however, I am talking to many of my white friends, I’m going to talk to them in terms I think they’ll better understand. I’ll talk about implicit bias. I’ll talk about how we have more in common in our fights than we do differences. And I’ll talk about black friends of mine and their jobs and what I know about them.

If need be, however, I understand BLM and what it’s trying to do and can talk about my support for it with my black friends. On this issue, as with almost every issue I care about, I can talk about the need for different strategies. I often argue, for example, how important it is for white people to be seen as part of the fight for equality and justice in the black community. We have to get involved.

Always though, I think of my audience and try remember the advice of other successful activists of the past: “You have to start where people are, not where you want them to be.”

The LGBT movement

When I think about symbols and slogans of the LGBT movement, what first comes to mind is the symbol of the rainbow flag. It’s the very definition of inclusion: All colors, all people.

When Marchall Kirk and Hunter Madsen, authors of After the Ball: How America Will Conquer Its Fear and Hatred of Gaysin the 90s, set out to cover bigotry, they realized that they were up against a majority with some pretty heavy anti-gay sentiments. Their argument in After the Ball is for a moral fight, a fight for equality that showcases how gay people are more like everyone else than different. They argued that many of the behaviors of prior pride parades focused on what much of America would see as deviant.

If the gay movement wanted to win people over to its side, it was going to have to be seen as moral.

What did they do?

They fought a publicity fight. They put the most normal gay people imaginable front and center of the movement. Kirk and Madsen’s efforts are why we see leaders like George Takei and Jim Obergefell today.

The 99 percent

In October 2011, I’d been blogging on Daily Kos for a couple months when I heard about this action going on in New York City called Occupy.

They had a slogan (“We are the 99%”) that immediately drew my attention. “This … this was the fight that might speak to enough people,” I thought. I wrote a piece called “99%: A Warning to #OWS and the Rest of Us” that ended up on the front page of Reddit and was my first introduction to the power of the Internet when it comes to movements.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was thinking about the division line exercise. The article was nothing more than encouragement to keep fighting this fight. I wrote the following:

As hard as this may be to believe, the 99% message may encourage some non-traditional (for Democrats anyways) allies who share the same frustrations: members of the Tea Party, small business owners, and members of the Republican party who may be dissatisfied with their party’s lack of new ideas for dealing with the economy.

“We are the 99%” is a fight we should not back away from despite the attempts (and you know more are coming) to divide the electorate differently to keep those in power in power.

I think one of the reasons Occupy eventually faltered was that it lost this focus. Popovic feels this way as well:

With just a simple name change, the Occupy movement could have shown themselves welcoming of many people: the urban, the rural, the conservative, the liberal,the short, the tall, the drivers, and the pedestrians. I would have loved to see that happen.

And yeah, I know that there were many efforts aimed at splintering the movement into factions and branding it as violent. We’re going to face these efforts regardless.

One thing that can help us overcome them, however, is to start with the division line exercise. Think about how we can bring the most people over to our side. Keep unity in mind from the start.

Actions

I believe corporate special interests have gotten so powerful and own so much media that the only way a movement is going to succeed in America is if it’s a mass-distributed movement. That is, it’s going to have to be a movement of 1 million leaders.

I write about this topic because if I’m right, we’re going to have to figure out ways to work together.

Popovic asks the question I’ve seen many of us ask, including the Democratic Party: “How do you ensure unity?”

The short answer is that you can’t. People will fight for you if you care about them and you care about what they want to fight for. Up to this point, some folks will be reading this and saying to themselves, “He wants us to drop our cause and pick up the cause of the 99 percent.”

This is not what the division line exercise is about. The division line exercise is about trying to figure out how to get as many people to fight with you as possible. It’s about thinking about others rather than thinking about your cause. This is what great leaders do to further the causes they care about. I care about creating great leaders (because I think we’re going to need a lot of them).

To be very specific, here are some recommendations if you are an activist:

- Talk to people from as wide a background as possible and ask them what they’re interested in and what they care about. Don’t try to tell them what you care about.

- Get as many people as possible from your cause to do this.

- Outline the things they care about.

- Run the division line exercise with people you know. Ask them, how could you bring people over to fight with you on something? (NOTE: This is very different from “How do I get them to agree with me?” The division line exercise focuses the conversation on getting people to fight with you.)

- Look at other causes and what they care about. Learn how to talk to them. At this point, I can talk about almost any issue with people. Sometimes I’ll fold this into a 99 percent conversation. Sometimes I won’t. Often I’ll offer to fight with them. Sometimes I’ll ask for help with something I’m interested in. It depends on the audience. What goes a long way is simply understanding what they care about and being able to repeat it. Not what you care about. What they care about.

- Use the division line exercise to figure out what’s going to work for your cause. Harvey Milk figured out that people in San Francisco cared more about dog poop than gay rights, for example.

And remember, if you want to build a big movement, pick a big fight.

Like Popovic, I’ve found that the 99 percent conversation is one we should still be having. It cuts across every other issue because the marginalized are often the folks who suffer most from the divide-and-conquer strategies of the 1 percent.

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy (ebook now available). Cross posted at Daily Kos.