Economists discover people don’t behave rationally

“Contrary to our original thinking, I’ve come to believe that people don’t behave like the economic textbooks say they should behave,” wrote Dr. Paul Wingfield, an economist at Cato University. “People don’t behave rationally.”

Wingfield and his colleague, Dr. Summer Redaction, recently published an article inHigher Economics titled “Outside our corporate think tank, people may not think as rationally as we think they do.”

To come to this conclusion, Redaction and Wingfield spent a summer in the field observing people and trying to understand them.

“It started,” Wingfield said, “when I observed a young couple making out on a park bench and I thought to myself, what a completely unproductive use of labor. Is there something I’m missing?”

This led to Redaction and Wingfield’s eureka moment: Textbook economic models make a lot of assumptions about the behavior of people.

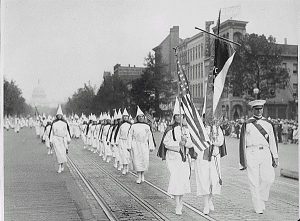

Ku Klux Klan members march down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. in 1928 (National Archives and Records Administration).

“People behaving emotionally,” Redaction wrote, “might explain road rage, white supremacy, binge drinking, bank runs, and even couples making out in the park. Perhaps our economic models were wrong.”

Other examples of non-rational behavior identified by Redaction and Wingfield include:

- Pet ownership

- Mid-life crisis purchases like convertibles or Ferraris

- Impulse buys

- Smoking

- Remaining in bad relationships

- Market panics

- Religion

- Donald Trump

- Fashion

- Climbing Mt. Everest

- Bucket lists

- Children

Their thesis went against 40 years of commonly accepted thought and many economists remain skeptical.

“The economy regulates itself like a machine that never needs fixing,” Chicago school advocate Gene Alan Danderspan said on CNBC’s popular primetime show, Don’t You Worry About the Economy. Danderspan also declared that Wikipedia, anonymous gift giving, and churches should not exist according to his calculations.

In the face of such criticism, Wingfield and Redaction replied that these things do indeed exist. These two economists have even started to wonder why so much money is spent by special interest groups like the Heritage Foundation, Cato Institute, the American Enterprise Institute, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, all trying to convince people to leave the economy alone.

“Could it be that some large corporations and special interest groups are acting selfishly and not in the best interests of the public?” Redaction and Wingfield noted.

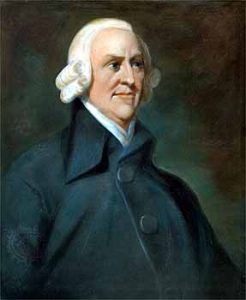

Their work builds on the work of early economist Adam Smith, who wrote inThe Wealth of Nations that wealthy business owners often work in their own interests and that we should be wary:

To widen the market may frequently be agreeable enough to the interest of the public; but to narrow the competition must always be against it, and can serve only to enable the dealers, by raising their profits above what they naturally would be, to levy, for their own benefit, an absurd tax upon the rest of their fellow-citizens. The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.

Redaction and Wingfield’s copious research supports the idea that business owners may tell you not to do what they themselves are doing. You, consumers: You should leave the economy alone. But for us, good men of industry, it is no problem to spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year lobbying to write or eliminate rules—as long as they work in our favor.

In addition to the assumption that people behave rationally, some other common assumptions that economists make in their models are:

- That people have perfect information about all goods and services.

- That buyers and sellers are so small they can’t affect a good’s price.

- That people have infinite desire for ever more goods and things. In reality, once people have a certain amount, demand tends to fall off.

“Perhaps economic models are just ways that we use to make a few predictions,” Wingfield and Redaction wrote, “but maybe we should use more common sense and history when it comes to policy decisions about the economy. Maybe we should look at what actually happens.”

After publishing their groundbreaking research, the economists added that they are looking for new jobs after being released from Cato University.

Note: In case there’s any question, the above is a satirical account of research that doesn’t exist. In reality, most economists actually do understand the assumptions underlying economic models. However, the “economists” we typically see in the media tend to be in the media on behalf of the people they work for, who represent corporate special interests. They tell us things without much basis in reality like “markets regulate themselves” and “tax cuts create jobs” and that we should “leave the market alone.” They tell us these things because they are paid by corporate special interests to create conditions that will increase the profits of a few. They do not represent what would be in the best interests of the public, and, as Adam Smith suggests, we should regard their suggestions with “suspicious attention.”

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy. Cross posted at Daily Kos.