Why regulations increase when you privatize government

Every now and then some politician pulls a stunt where they print out a list of regulations from some agency or other to try to make the point about the “burden” of regulation.

Mitch McConnell speaking at the CPAC 2011 conference. Photo CC 2.0 courtesy of Gage Skidmore.

What they don’t talk about is that privatization creates more regulations.

Why?

We’ve been “freeing” markets ever since the 1970s and 1980s as Chicago School ideas, led by Milton Friedman, came to dominate the public imagination.

This idea that the private sector can do better (at anything apparently) than government is the driving ideology of our time.

We should be evaluating some of the claims of this belief.

Here, I want to look at one specific claim. This idea that privatization of government leads to less regulation. The reason for looking at this belief, in particular, is that people don’t like regulations. There’s a very visceral reaction to Rand Paul chain sawing the IRS tax code or Mitch McConnell or John Boehner standing there with stacks and stacks of regulations from the Affordable Care Act.

What Paul and McConnell and Boehner don’t tell you is that these regulations are often a direct result of privatizing public functions.

In his book The Utopia of Rules, David Graeber refers to this principle as the Iron Law of Liberalism:

The Iron Law of Liberalism states that any market reform, any government initiative intended to reduce red tape and promote market forces will have the ultimate effect of increasing the total number of regulations, the total amount of paperwork, and the total number of bureaucrats the government employs.

Let me explain why this is the case through some examples.

Education privatization in Ohio

Charter school companies in Ohio have been working with the Kasich administration to privatize more and more of our public schools.

They’ve funneled donations to politicians to write the rules in favor of charter school companies like White Hat Management and Concept Schools, Inc.

Writing the rules in their favor looks like this: ‘

- Charter school companies get the contracts

- There is no oversight of charter schools

- Oversight is used to try to “regulate” public schools out of existence by putting in place impossible standards for them to meet

Ohio revised code exempts charter schools from over 150 public school regulations:

3314.04 Exemption from state laws and rules. Except as otherwise specified in this chapter and in the contract between a community school and a sponsor, such school is exempt from all state laws and rules pertaining to schools, school districts, and boards of education, except those laws and rules that grant certain rights to parents.

The idea was that the “market” would somehow regulate itself.

Except the problem with this thinking is that the primary purpose of charter schools is not education. The primary purpose of these companies is to return profit to shareholders.

This creates a conflict of interest where these companies try to figure out the cheapest way possible to achieve high test scores. In some cases this is tampering with test scores, in other cases it’s simply getting rid of potentially low-scoring students.

Incentives do matter. And there’s no incentive to actually provide an education to students.

What’s happened under this arrangement?

Ohio schools have dropped from 5th to 18th in the nation since John Kasich has taken office in 2010 and the state has seen scandal after scandal from charter operators.

David Hansen, school choice director for the Ohio Department of Education, resigned after leaving out F grades for online schools. Horizon Science Academy in Cincinnati is being investigated after reports from former teachers about sex games, unqualified teachers, and test tampering. White Hat Management wrote contracts with school boards that essentially allowed White Hat Management complete ownership of property purchased with public money.

The Fordham Institute, a corporate special interest group that advocates for charter schools, even called Ohio the Wild West and advocated for reform.

In response to this black market mess, Ohio recently passed charter school reform: Substitute House Bill 2. The conflict between profit and mission is where all these regulations come from.

We know that without bureaucracy, corporations will cheat people for profit.

With public schools owned by people, schools are responsible to people and to the local communities.

With privately owned schools, the schools are responsible to owners and profit unless a government bureaucracy is created to manage and ensure these schools don’t abuse their power.

The need to ensure corporations don’t abuse their privilege creates more regulation. Privatization creates public-private bureaucracy and overhead.

Sarbanes-Oxley

Sarbanes-Oxley is another great example of how supposedly “freeing” a market created more bureaucracy.

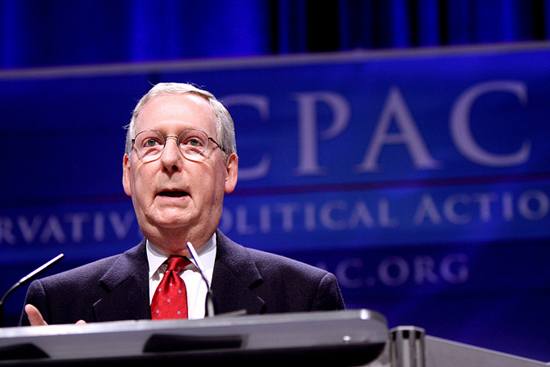

You may remember a couple of companies named Enron, Worldcom, and Tyco International. A major part of the scandal involved in the collapse of these companies was that they were lying to shareholders about their performance. Enron, for example, created hundreds of special purpose entities that allowed the company to hide Enron’s debt while giving Enron control of the assets. The company had off balance sheet debt that was more than double what it reported.

Enron stock price from August 2000 to January 2001. Chart CC3.0 courtesy of Nehrams2020.

In other words, in the absence of regulations, companies cheated. Not only that, but companies cheated because it made them hugely successful. And auditing companies that were supposed to have discovered the cheating were in on it. At one point, Enron was one of the most admired companies in the world. Huge incentives existed for the company to cheat.

How did we deal with the “free” market?

We passed legislation and regulation. In other words, we created a bureaucracy to make sure that companies wouldn’t cheat.

The free market leads to either collapse (when the pyramid schemes fall apart) or bureaucracy.

We saw the same thing with the financial crash. When we lifted restrictions on banks and financial firms to allow them to combine, almost immediately these firms started using public funds to finance risky investments.

When incentives exist for corporations to abuse trust, regulations increase. This is the case with so-called “free” markets.

The Affordable Care Act

The bogeyman of criticism in current conservative circles is the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

All the regulation is supposedly hampering the “free” market. The problem with this critique is that before the ACA, we saw the free market at work. 30 million+ people without health care. Emergency rooms used as primary care providers. People kicked off health care and unable to get new policies because of pre-existing conditions.

These things happened because the primary purpose of these organizations wasn’t to provide health care for people. It was to profit.

Health care companies found that the easiest way to profit was to sell insurance to the healthy and not have to pay out any benefits. In other words, we’re there for you when you don’t need us. When you need us, we’re going to drop you.

CCBRT Disability Hospital waiting room. Photo CC2.0 courtesy of Department of Foreign Affairs.

This was the state of health insurance. It was a miserable free market failure:

- The U.S. spent 17% of GDP on healthcare – the most expensive in the world

- 30 million people without insurance

- Insurance was denied

- People went to emergency rooms for primary care

- The U.S. was quickly falling behind other countries when it comes to life expectancy, infant mortality and patient satisfaction

There were several options available to fix this problem. One of the options was to take the profit motive out of insurance and return insurance to the public interest. This idea was defeated by lobbying from the for-profit insurance companies in favor of market reforms.

If you want a working market for health care, the person who wrote the book on the subject was Nobel-winning economist Kenneth Arrow. In 1963, he published an article talking about the problems with health care markets. To summarize a few of the main points:

- Unlike most goods and services, people don’t know when they’ll need healthcare.

- When people do need healthcare, it can sometimes be very expensive (ex. heart failure).

- The cost of care is typically not known by patients. This increases the leverage of the healthcare industry over consumers and is sometimes why you’ll see differences in price in different locations throughout the U.S.

Numbers 1 and 2 make it very difficult for people to simply have the money available for healthcare in a manner similar to fires or natural disasters. This is why systems are typically based on some type of risk pooling and insurance model.

Given an insurance model, you simply can’t have people opting in and opting out when they feel like paying.

The failure of the market to insure against uncertainties has created many social institutions in which the usual assumptions of the market are to some extent contradicted. – Kenneth Arrow, 1963

What do we know?

We know unregulated markets don’t work. We know the insurance companies blocked taking the profit motive out of health care. This left the option of creating a different market and passing a law to require insurance.

To create this market and prevent abuse of it requires …. guess what?

That’s right. Regulation. A market solution for health care requires regulation.

If we wanted less regulation, we’d need to take the incentive for abuse, the profit-motive, out of the equation. If insurance companies were non-profits with the goal of helping people instead of returning money to shareholders, there would be less incentive for abuse.

British economist Ronald Coase introduced the notion of transaction costs. Transaction costs, quite simply put, are costs of using the market. In other words, in addition to the cost of the good, there are also costs associated with using the market. Some of these costs include:

- Information costs

- Bargaining costs

- Keeping trade secrets

- Policing and enforcing

- Costs associated with establishing contracts

Sometimes the cost of obtaining a good through the market is more than the price of the good. Coase’s theory explains why companies exist. Sometimes it’s more efficient to hire someone, for example, than to simply contract with this person through the market.

With health care markets, some of these transaction costs occur as a conflict between the conflicting incentives of profit and delivering quality health care. In other words, regulations need to exist to make sure health care companies don’t abuse their power in the name of profit. Other related costs include bargaining with the health care companies and policing and enforcing the solution.

In a non-profit or government-run situation, this conflict of interest wouldn’t exist. It would be much easier to trust that insurers would work towards the public good.

Private companies see their transaction costs go down when they can establish trust with customers. When both sides trust each other, the need for contracts, bargaining, policing and enforcement goes down. Management overhead decreases.

We would see increased trust with insurers if they didn’t face conflicting incentives. If these organizations were non-profits, the need for bargaining, contracting, policing, and enforcement bureaucracy would decrease. In addition, we wouldn’t have to pay for private company profits for services in the interest of the public good.

So, oddly enough, the people who should be out there with the chain saws are liberal.

—

|

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy. Follow @akadjian |