The importance of fighting with someone on something

Students from Texas Tech University build a house for Habitat for Humanity in 2010. (Texas Tech, Habitat for Humanity, 2010 – CC-BY-2.0)

In 1954, social psychologist Muzafer Sherif ran an experiment that could not be repeated today. Sherif was investigating prejudice and contesting Freud’s model of prejudice as an acting out of unresolved childhood conflicts.

At the Robbers Cave Boy Scout camp, Sherif wanted to test whether he could take a group of people, without any inherently hostile attitudes towards each other, and create conflict by introducing competition.

What Sherif found was not only that he could, but that he could also resolve the conflict if he introduced a shared goal. As I talk to people about politics and work for change, I always try to remember the importance of fighting with someone on something.

What happened at the Robbers Cave

Sherif and his researchers recruited 22 boys for a three-week summer camp at Robbers Cave State Park. None of the boys were told they were going to be a part of an experiment.

The boys were broken up into two groups called the Rattlers and the Eagles. During the first week of camp, in their separate groups, they did what most kids do at summer camp: They hiked, they swam, they canoed, and they cooked out. By the end of the first week, both groups had become cohesive teams.

Rattlers with banner reading “The Last of the Eagles.” (Sherif, “Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation”)

In the second week, the experiment began as the researchers introduced competition between the two groups. They played baseball games against each other and fought in tug-of-wars. Then the taunting began, first with name calling and then with identifiers, such as a flag the Rattlers placed on the baseball field after winning a game. The Eagles burned the flag and put it back up on the pole. Fights even broke out between the kids and they raided each other’s camps. After a week, the two groups viewed each other as complete enemies.

In the third week, the team wanted to see if they could reunite the two groups of warring kids. How did they do it? They introduced a series of seven unifying tasks that could only be achieved if the kids worked together.

First, they made a water tank “break down” and asked the boys to search the entire line in a coordinated effort to find the blockage. All the boys volunteered and eventually they found the “break” and they all helped to remove the blockage. They also created a situation where a truck that was going to get food needed a push to get started. They tied a rope around the truck and all the boys pitched in to help give it a pull-start. By the end of this third week, all the kids told stories and sang together around a campfire.

The lesson is that leaders have the power to unite separate groups by the actions they take. Leadership is about uniting people.

I’ve learned that I can do this on an everyday basis if I’m simply open to the opportunities and willing to step out of political differences (how similar are “Rattlers” and “Eagles” to Republicans and Democrats?).

My personal nemesis

I’ve been having political conversations with a guy I’m going to call Jack for almost 10 years.

Jack is ex-Army and is an expert at trolling liberals online. I don’t know anyone better at this than Jack. He truly has a way of getting under liberals’ skin—I think he got a degree in trolling. It wasn’t long before I realized that I wasn’t going to convince Jack about much of anything.

One day, Jack posts a question about an argument he’s having with his wife. Because he posts at this one particular site so much, we all know him and often we’ll talk about stuff other than politics. He asked for help in winning the argument.

I asked him:

Do you want to win the argument or do you want to be happy?

Jack really liked this answer. It was funny. It made him think about what really mattered to him and genuinely helped him. He had to admit that when he thought about it, it wasn’t that important to him to win the argument. Sure, the advice is a bit cliché. But he hadn’t heard it before and it gave him a way to justify what he might before have thought of as “weakness.” Now it was humorous.

A couple of years later, I hopped on the political site and Jack tells me his daughter just got married. He said as part of the toast, he told the story about the advice I’d given him and how he was passing it on to his son-in-law.

We still don’t agree on a number of things but he’s willing to listen and we at least have a basis for mutual respect and trust.

Working together with people is powerful. It builds trust (in a world where we’re so often pitted against each other). And if you can establish trust, it’s also surprising sometimes how much better your political conversations get.

Now it’s important to do this honestly. I didn’t offer the advice to try to win any political argument. I just did it because he asked honestly for help and I thought I could help him.

Fighting with Christians and evangelicals

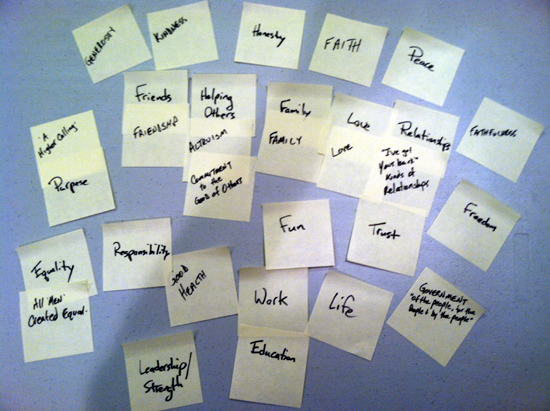

If you take the question about God out of the equation, liberals and Christians/evangelicals often have very similar values.

We believe in helping people. We believe in compassion. We believe in family. We believe in peace, honesty, responsibility, work, life, good health, education, and purpose.

It’s almost funny how we show up at all the same types of events: Habitat for Humanity, the Freestore Foodback, helping out at homeless shelters, etc.

At these types of events, I like to find ways to come out of the closet as a liberal after I’ve gotten to know someone. I’ve had all kinds of people act surprised after I told them that I was just there because I’m liberal. This is good. This changes perceptions.

I’ve also had some really good conversations that go further after they realize we can actually talk.

Another good conversation to have with Christians and evangelicals is about family values. One, it’s a conversation they’re very comfortable having but not something they often hear about from “liberals.”

Once I’ve established some level of trust, I’ve even gone so far as to specifically ask:

What values do you have that I don’t?

This is a tough question, one that you have to gauge if you can ask. But if you can ask it, it’s powerful because the answer is typically: We’re pretty much the same. We have some differences when it comes to believing in god, but in terms of values, we’re pretty similar.

I’m okay with that because I believe in freedom of religion and am much more interested in what we can fight together on.

Another thing I will often ask Christians is: Will you fight with me for freedom of religion? This is a great intro to talking about freedom of religion (not freedom of your religion, but freedom of religion).

Fighting with libertarians and conservatives

I like to think libertarians are really just liberals who are afraid to say they’re liberals. Or liberals who’ve been taught that all bureaucracy somehow resides in the government instead of also in most of the big-to-medium-sized corporations they work at.

Anyway, a number of issues I’ve fought with libertarians on:

- Against for-profit prisons

- Against the Trans-Pacific Partnership

- Against surveillance

- For decriminalization of marijuana

- Against revenue raising schemes on the poor like speed cameras

Again, it’s important here to also use these fights as a chance to lead and have other conversations. Libertarians tend to mean well—they just believe in a machine-like view of the economy. That is, instead of thinking that markets should serve people and make our society better, they tend to think in terms of how we could make some economic model they have in their heads work better.

The thinking is that if somehow we could just work out the kinks, it would automatically lead to a better society.

In other words, we serve the model instead of the model simply being a model that sometimes predicts how things work, and sometimes doesn’t.

What I like to talk about is how people create markets. We started out bartering and then we invented money as a more convenient exchange medium. We created rules for fair trade that include banning human trafficking and slavery. We don’t allow people to purchase nuclear fission material. We have laws against monopolies.

If people can see markets as something we create, then it seems reasonable to think about the end goal of these rules. Should we be creating markets to benefit everyone or should we be creating them to benefit just a few?

Some questions I like to ask include:

- How would you break up a monopoly?

- What’s one regulation you would get rid of and why? (I do this because I so often hear there’s just too many regulations and this never gets questioned. Sometimes this question actually leads to really good conversations about regulations that we could possibly eliminate. More often than not, however, it’s pretty easy to point out how it’s needed.)

- Does it bother you to stop at traffic lights? (Just to point out that mean old gub’ment sometimes has a purpose.)

- If we agree that there need to be rules for markets, what’s the best way to establish them? Do you decide? Do I decide? (This sets up the case for democracy actually being not only useful but necessary—if it weren’t so corrupt.)

If you can genuinely ask people to explain something, it leads to much more thinking than any kind of back-and-forth attack. I say “genuinely” because it has to be done in the spirit of trust and interest, rather than in the spirit of trying to “win.”

So I only have these types of conversations once some trust has been established.

Coda

I’m often accused of being “nice” to “these people.”

No joke. I swear this is the language that’s often used. It has nothing to do with being nice. It has everything to do with a couple of things.

First, I’m much more interested in what we can work together on.

And second, I understand that we’ve been pitted against each other—whether we like it or not. One way to “unpit” us is to start with something we can work together on in order to build trust before having harder conversations. It really doesn’t matter what this “thing” is.

I think one of the mistakes we often make in our personal political conversations is that we start at the wrong point. We tend to start at confronting people instead of starting with building trust. We probably do this because this is the battle that’s played out for us on a day-to-day basis in the media.

What might make good media strategy often makes for terrible, unproductive personal conversations. This is why it’s important to fight with people on something.

—

|

David Akadjian is the author of The Little Book of Revolution: A Distributive Strategy for Democracy. Follow @akadjian |